Predictably, The New York Times is suing Open AI and Microsoft for copyright infringement. OpenAI has used The Times' text to train their large language models. I have no opinion on the legal merits of the case. Courts will try invent some line between fair use and infringement under existing law that balances various interests in this brave new world of LLMs.

But I hope that Congress will act to address the question more holistically and creatively than courts can. Here is my two point plan for what Congress should do:

-

Congress should declare that big-data AI models do not infringe copyright, but are inherently in the public domain.

-

Congress should declare that use of AI tools will be an aggravating rather than mitigating factor in determinations of civil and criminal liability.

Congress should declare that big-data AI models do not infringe copyright, but are inherently in the public domain.

The moral justification for this is clear. Big-data AI models are summarizations of the work of large publics. They are a whole much greater than the sum of the parts. Their value comes from a public much too broad and amorphous to constitute an identifiable party who might license inputs or be compensated.

The law should explicitly reject claims like Adobe’s that, by training models on only work explicitly licensed to them or in the public domain, they address this concern. Even if every individual input dots the i's and crosses the t's of prior copyright law, modeling very large corpuses of work extracts information not only from the direct inputs summarized, which might in theory be compensated, but from all the inputs and influences to the creators of those direct influences.

These models are not simply new creative works derivative of particular other works. The modeling process is something new, a tool designed to extract regularities and patterns and ideas that characterize the domains they model as a whole. The training set is a telescope and a microscope. Their object of study is human creation very broadly, and these fruits of human creation can belong only to humanity writ large.

In order to immunize themselves from claims of unlawful expropriation, including both old-school copyright claims and new claims on behalf of the public itself, anyone who trains AI models would have an affirmative obligation to publish and place into the public domain both the results of their training — the “weights” — and the structure of the model under which those weights take their meaning, including code, such that people of ordinary skill in the domain could quickly stand up and run new instances of the model.

This would, you might object, take away some of the incentive to train large models. It would. But the commercial incentives to develop AI models are already very strong. The Microsofts of the world that want to integrate AI tools into their products can easily afford to fund them as loss leaders. Business communities more broadly, who perceive opportunities to increase productivity or reduce labor costs, would find that pooling resources to train open-source models easily pencils. Academics and the public sector would train public models as well.

On the other side of the training set, you might object that putting these models in the public domain does nothing to put food on the table of the creators whose work is ingested to produce them. That is very true. But it is a common result of new technologies that old activities that once were remunerative cease to be so. Marc Andreeson is wrong to imagine that inherent characteristics of technology and capitalism ensure that as some means of subsisting are eliminated, better and more remunerative jobs are sure to replace them because of higher marginal productivity or whatever. At an individual level, many people whose work has been technologically obsoleted suffer harms from which they never fully recover. At a broader level, only the expansion of social democracy has rendered technological development and something like full employment remotely compatible.

Widespread use of large-language models will demand a more redistributive state, as much of the public will find these models undermine their (our) current source of market power and therefore ability to command a decent wage. Nevertheless, it remains true that, with decent governance, we are collectively better off when we can all do more with less human work. The right way forward is to continue to let technology make us, in this narrow sense, “richer in aggregate", but use the institution of the state aggressively to ensure that richer in aggregate means all of us live better lives and none of us bestride the narrow world like Elon Musk.

AI models do nothing at all to hinder human creativity. For many people, generative AI will enable, has already enabled, new means of creative expression. But what is less scarce is less valuable in commerce. It is not creativity that is threatened, but the creative professions.

I don't think we want market forces to turn 90% of today's creative professionals into nurse's assistants, plumbers, and staff for upscale resorts. Art lives not just in its artifacts, but in collaborative relationships between human artists and audiences, and in forms of collaborations where roles of producer and consumer are less distinct than those terms suggest. The value that we derive from creative work is not independent of who produced it and how. Creative work constitutes the symbols and sinews of human communities. It is the substrate, scaffolding, upon which we develop our notions of the sacred.

Creativity and capitalism have always sat awkwardly together. They will now sit even more awkwardly. There will be no papering over the divergence between exchange value and value. I don't think we should romanticize the era that is ending. The imperatives of remuneration have recruited beautiful hearts to compellingly sanctify arrangements that are horribly profane. There have been so many beautiful ads.

We will all still need to eat. We will be less able to pretend that "free markets" can somehow reconcile meeting that need with performing our highest purposes. The challenge we face has always been political. I think it's neither wise nor virtuous to try to suppress generative AI in order to retain a status quo under which some of us could pretend that it was not.

Congress should declare that use of AI models is an aggravating rather than mitigating factor in determinations of civil and criminal liability.

AI models clearly have a lot of potential uses. But they just as clearly could cause a great deal of harm. AI models can launder what we might otherwise recognize to be invidious discrimination by race or sex. They can render “objective" or “rational” the murder of children en masse. They can run down pedestrians and then, in their digital confusion, drag them for twenty feet.

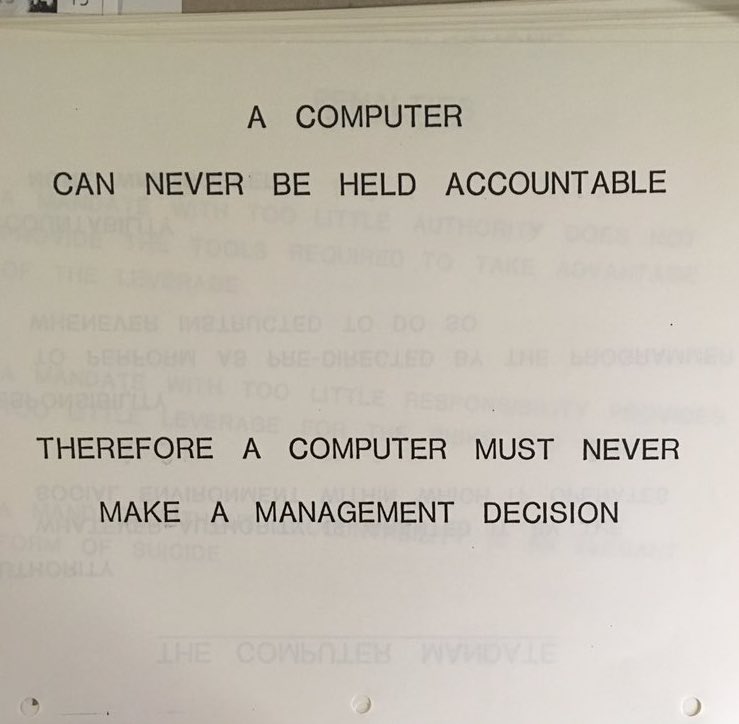

There’s that slide, usually attributed to an IBM presentation from the 1970s, stating “A computer can never be held accountable, therefore a computer must never make a management decision.” No sentence ever has more completely misunderstood the imperatives of management. Managers, who are inevitably made responsible for much more than they can control, constantly, desperately, seek means of escaping accountabilty for the decisions that they calculate will be in their interest. An entire, storied industry is based upon serving this compulsion.

If the public allows it, the first and most important use of LLMs will be to allow managers, firms, and governments to shirk accountability, either by deferring to the expertise of "objective” models, or by blaming inevitable, regrettable glitches that of course we must accept for the greater good while developing any brilliant new technology.

So the public, via the state, must not allow it. Commercial users of AI models will argue that the law should treat occasional “mistakes” resulting from AI model outputs to be unintended and unforeseeable outcomes of ordinary business processes, for which their liability should be minimal. If the self-driving car hits a pedestrian, that is regrettable, but of course there can be no criminal charges, as there might have been for a human driver who dragged a person 20 feet after striking her. If lots of people are wrongfully denied insurance claims by some black-box model, eventually perhaps some class-action lawsuit will succeed and make some lawyers rich and fail to bring back the dead. The firm will pay a financial settlement, a cost of doing business. Of course, if a human had systematically made the same error, and it was in the firm's or their own financial interest, the human might have been convicted of fraud. But a computer is eternally innocent.

We should not treat computational models — of any sort, but especially models as unpredictable as LLMs — as legitimate and ordinary decision-making agents in any high-stakes business process. A computer cannot be held accountable, so the law must insist that, by definition, it is never a computer that makes a management decision. If it seems to anyway, and then it errs, the humans who deployed it were presumptively negligent. If it errs systematically in the interest of the firm, its human deployers were presumptively engaged in a conspiracy to defraud.

An analogy I like to use is alcohol and driving. One way we could think about a person who causes a fatal car crash while intoxicated is that they did not have their wits about them, they did not intend to do the harm. It was a tragic accident when they were not at their best, so their culpability should be limited.

Another way we can think about the same event is that precisely because after drinking a person would foreseeably not have their wits about them, the very act of drinking without making alternative transportation arrangements increases their culpability for the accident. They should have known well in advance of the tragedy itself they were doing something risky. The risk that they took was essential to the crime, not just the fact of the horrific consequence.

Each of these framings is legitimate. They just express different social values. If, as a society, we place a very high value on the joys of alcohol-lubricated conviviality and our liberty of automobile-mediated assembly for that purpose, then we might treat intoxication as a mitigating factor in car accidents, and accept their prevalence as a price we pay for a greater good. If we don’t place so high a value on a good time, or we place a much higher value on reducing car accidents, then we would adopt the framing that we have, under which alcohol is an aggravating factor.

We face a similar social choice with LLMs. The business automation they might enable should be scored as a social good, to the degree they free humans to do either work only humans can do well or to enjoy greater liberty and leisure. But low-quality work and the risk of laundering fraudulent or unethical practices through an ablution of mysterious technology should be viewed as a grave social cost. There is no such thing as perfect balance. We have to decide whether to err on the side of license — on the theory rapid deployment of these technologies will make us richer and happier and better — or of caution, because we think quality of deployment outweighs any benefit of speed. Fifteen years ago, before our collective experience of social media and surveillance capitalism and platform peony, I would have opted for license. Now, however, I strongly favor caution.

Use of these technologies should not be banned, for almost any purpose. But our social presumption should be they are unreliable, experimental, susceptible to difficult to detect forms of abuse and predation by their deployers. Whenever things go wrong, their deployers are innocent until proven guilty only of the fact of deployment. Once it has been established that they have deployed these technologies in consequential roles, they become presumptively responsible, civilly and criminally, for all the harms wrought by systems they deployed but negligently failed to adequately supervise, or worse.

That presumption would be rebuttable. If deployers can show that the system they created performs at least as well, caused no more harm than, systems in common use that do not use the technology, then they have not been negligent. Waymo, for example, has approached autonomous driving with a great deal more caution than competitors Cruise and Tesla, such that in practice its cars have been much safer than human drivers. So long as this is the case, those responsible for deployment of Waymo vehicles should not be held liable, civilly and criminally, for reckless driving following the very few accidents involving its vehicles that do occur. Cruise and Tesla, on the other hand, would not succeed at rebutting a presumption of negligence.

The purpose of the proposed legal regime would not be to ban these technologies from business processes. It would be to insist upon their high quality, from a social perspective, and ensure that quality is placed before imperatives that might otherwise lead businesses to profit by externalizing risk and harms.

2023-12-28 @ 02:35 PM EST