The great "vibecession debate" continues. Is the economy good or bad?

Y'all know I think it's bad, bad now under Trump, bad even when people with my politics touted its virtues as Bidenomics.

Whatever.

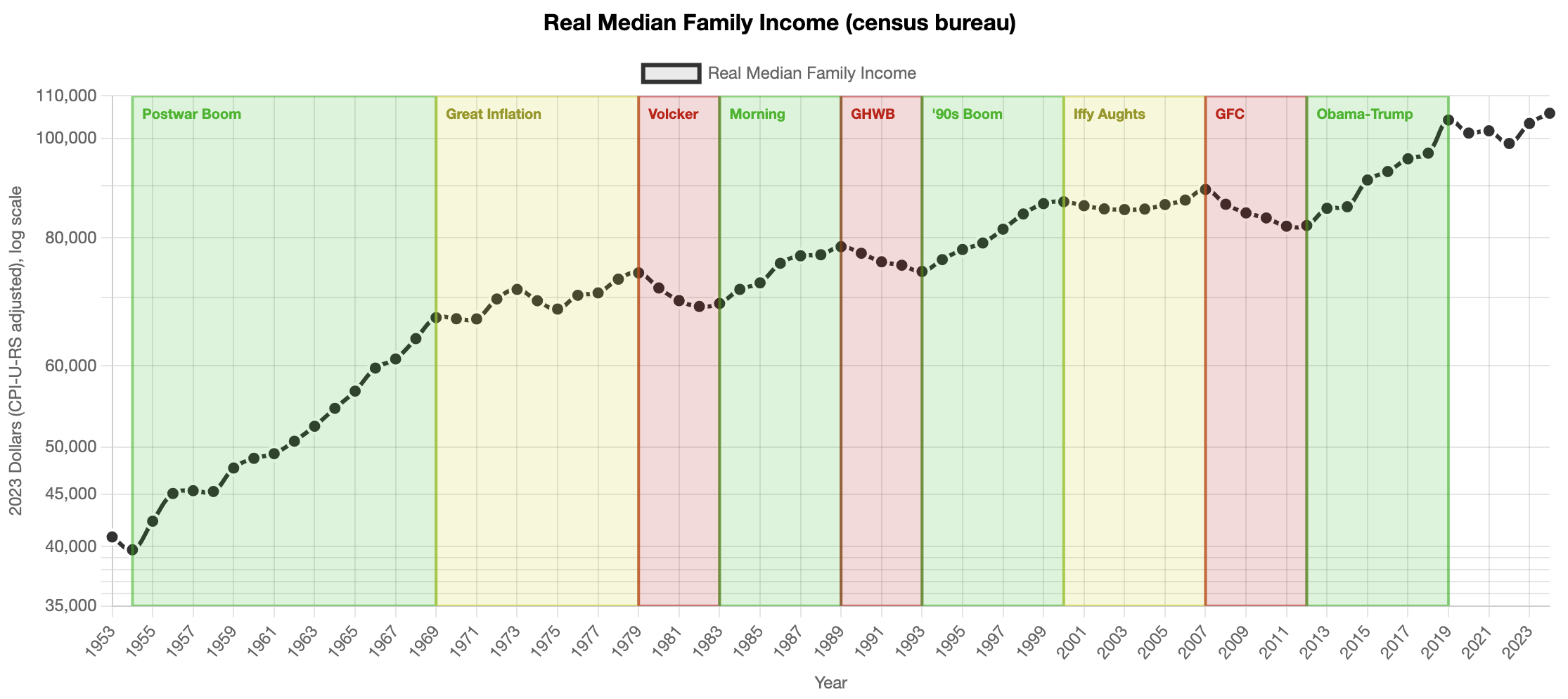

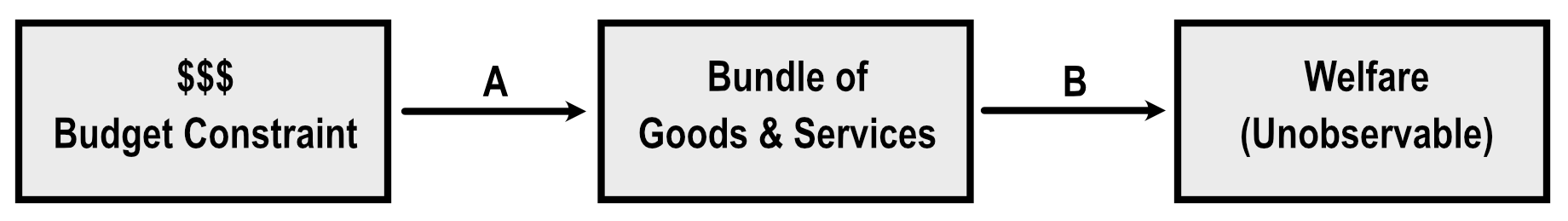

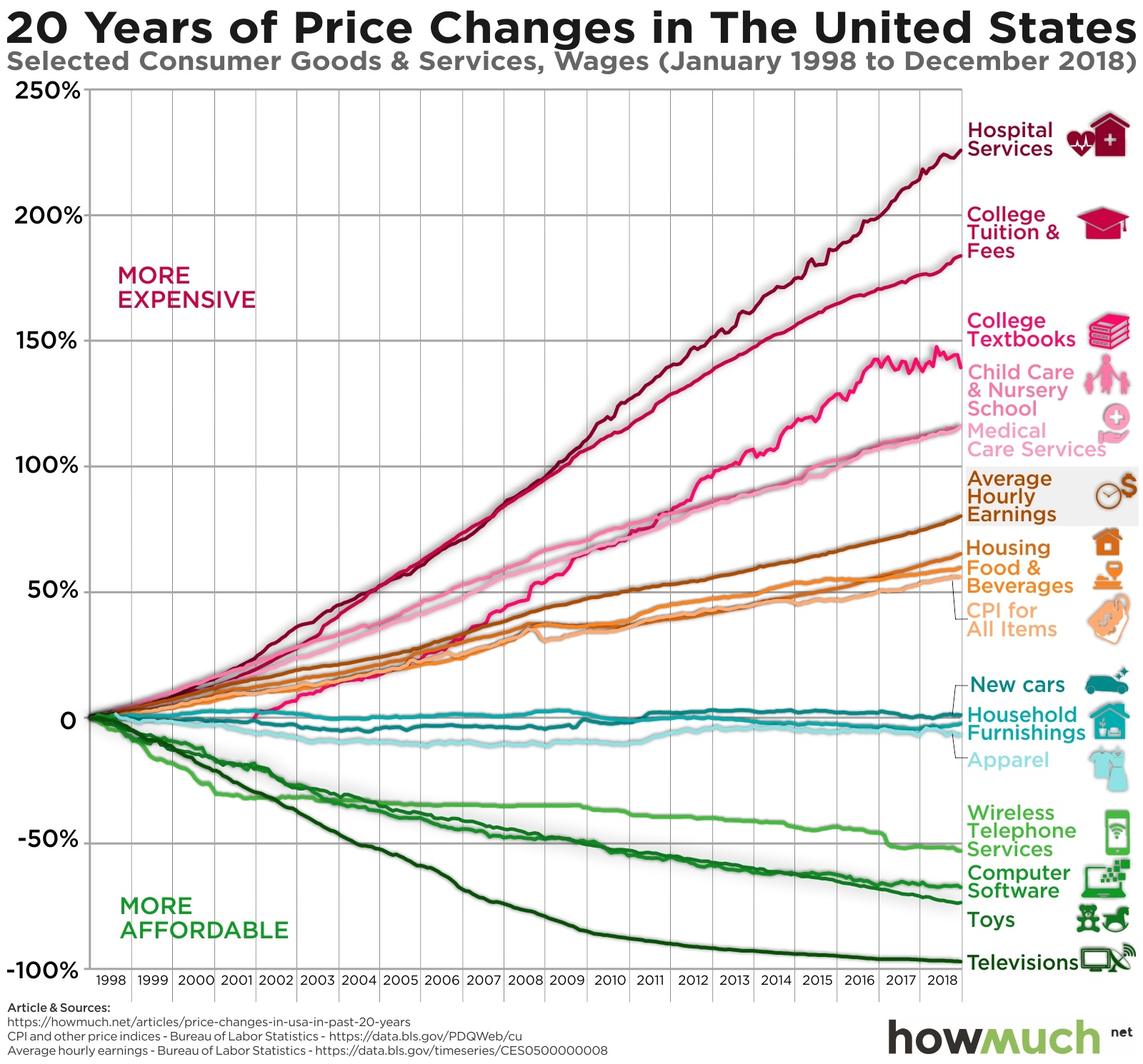

My purpose here isn't to take sides, but to offer a bit of a historical perspective on how we perceive the economy. Let's take a look at a chart:

This chart is of the census bureau's real median family income series.

I didn't choose the series because I think it is a uniquely valuable indicator, but because the "data guys" on the Panglossian side of the debate like to point to real median household income. Unfortunately, the household series only goes back to 1984, and I wanted to go back farther. The family series goes back to 1953.

The two are qualitatively very similar. The main difference is that single-member households are excluded from the family series, pushing the median income upward. (Income from unrelated individuals who cohabitate with a family gets excluded from the measure, pushing incomes down, but this effect is small.)

The first thing to point out, as I've tried to emphasize before, is there's very little information in the level of these series.

In 1978, real median income was apparently higher in absolute terms than it ever had been! It was true then, as it is now, that the typical American was living a lifestyle that the greatest kings and emperors of prior centuries could never afford. GDP per capita was growing faster than 5%, a rate we've only rarely achieved since. Yet very few people, then or now, would argue that the 1978 economy was great.

You can see trouble in the data, just other data. Arthur Okun, an influential economist of the era, invented the "misery index", and that was pretty high in 1978, although it had come down dramatically from prior years. But much more than then-current conditions, commentators at the time felt — with foresight ultimately vindicated — that the relatively benign moment was a lull in a continuing storm. Despite good data, it was a bad time.

You'll notice that I've divided my chart into eras, and the era to which 1978 belongs is shaded not red for "bad", but yellow for "meh". That is because I am data-driven. Most commentators would say that the period I've marked the "great inflation" was the worst economy of the postwar US except for the great financial crisis. But by the numbers, by these numbers, the period is only a slow-growth stagnation, comparable to the aughts.

The key point is that the goodness or badness of the economy is never an objective fact about the world. It is a thing we construct, in a project often contentious in real time, but that usually hardens into consensus ex post. During soft patches, we debate whether we are in or near a recession. After a while some committee at the National Bureau of Economic Research gives a verdict that becomes authoritative, if not necessarily true.

There are an infinity of potential data sources, many of which will tell conflicting stories. There is no consistent and universal set of weightings we can apply in order to evaluate the economy. Data sources exist today that could not have existed even a few years ago, like AI-generated evaluations of media sentiment. The stories we tell, the evaluations we give, are never science. They are pastiche. The quality of the economy exists in the netherworld between subjective and objective, in the purgatory of the judgment call, where we humans also reside.

Although there is almost no information in the level of this median real family income series, there is a ton of information in the changes. Despite a misclassification of the great-recession era, turning points in this series do a really good job of segmenting the economy into recognizable eras and marking them as "good" or "bad". That's how I've parsed out the eras on the chart.

I've graphed the series on a log-scale, so that slopes correspond to growth rates. Part of the apparent virtue of the graph results from a kind of look-ahead bias. I define a turning point at 1969 rather than a similar break in 1971 or the more defensible turning point at 1973 because I know that inflation begins to draw up its skirts in the late 1960s. I arbitrarily chose four years as my minimum length of an era, because I didn't want to segment out every leg of every business cycle. This forced my Volcker Shock to extend a year longer than a mechanistic segmenting of turning points would have yielded. Still, the graph is pretty close to a mechanistic segmentation, and marks out eras commonly understood and discussed surprisingly well.1

A few points are worth discussing. Just on the basis of this little exercise, it's unsurprising that we have nostalgia for the period from 1954 to 1969. In the history of the economy as represented by this one, imperfect, measure, there is no other period with the length and slope — the persistence and growth — of this period. "Make America Great Again" gets some of its rhetorical force from the fact that there really was, in living memory, a kind of golden age to yearn backwards toward.

(Much of this era was still under Jim Crow. But it was also when the civil rights movement bore its long-sown fruit. The period was riven by unrest and political assassinations. It was a time of remarkable music. Whether on balance it is reasonable to describe the era as a golden age is a judgment call that belongs to you, dear reader.)

I was very surprised to see that the only period that comes close to the postwar boom, in growth but not duration terms, is the Obama-Trump era, from 2012 to 2019. I will confess to you, dear reader, that my own subjective evaluation of this period would be "meh" to "bad". But by the numbers, by these numbers at least, 2012–2019 was the best economy since the postwar boom. Nevertheless, in 2016, in the middle of this apparently great period, the American people wanted a revolution. When the possibility of a benign revolution lost a Democratic primary, they chose a malignant one. Data is only useful if we remember to discuss what it omits as carefully and extensively as we describe what it seems to say.

Although I understood (and wrote ad nauseum about) the deficiencies of the Biden economy, I was surprised that restoring the Trump economy was compelling as a pitch to the American electorate. This data suggests I should not have been surprised.

Still. Was 2012-2019 a better economy than the 1990s boom? For those of you old enough to remember, I'll leave it to you to decide. We were all so much younger then. Is that the reason why it seems so wrong to me? I don't think so. I don't think a 28-year-old in 2018 had the kind of optimism about the economy that I had in 1998.

Today's "vibecession" debate is about how we will, or should, categorize the rightmost five dots on the chart. Based on this dataset alone, it's not surprising that we are arguing. If I were to draw a box around it, my mechanistic classification scheme would have it yellow, "meh". Sometimes we end up deciding the yellow periods are actually bad (the "great inflation"), sometimes we look back at them as decent if not amazing times (the "iffy aughts"). For now, at least through the lens of this dataset, it really is a "faces or vase" kind of question.

The period those last five data points most resembles is the late 1970s. The shape of the series is a similar, shallow "V", and for similar reasons, an inflation spike had eaten away at family purchasing power.

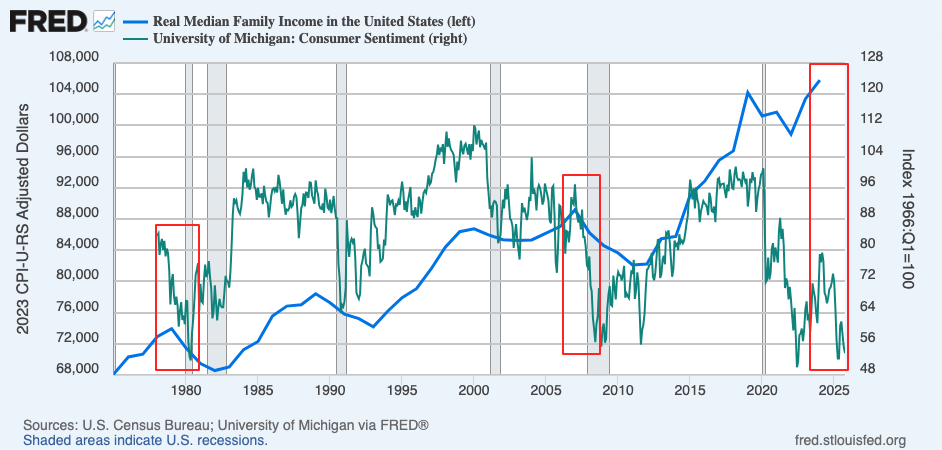

If we pair the series with Michigan consumer sentiment, we find the current pattern looks pretty similar to 1979 and 2007, peaks in real median family income followed by collapses in sentiment:

However good you think the economy is or recently was, if it's not just a vibecession, or if a vibecession can be self-fulfilling, the current set-up looks a bit ominous.

But let's end this with something cheerful!

A series not typically taken as an economic indicator, but that I like, is the suicide rate. I think the suicide rate is useful because it gets at welfare, which is properly the concern of normative economics, rather than "stuff", which is ultimately meaningless except to the degree that it contributes to welfare. King Midas could buy anything in the world, but he was not wealthy.

Welfare is a normative, rather than a positive or "scientific" concept. It is a thing we define, rather than measure. Nevertheless, it is what we care about, the ultimate object of our investigations, and in that sense welfare is more real than all of the things we can measure.

Once we have imposed a definition, we can try to measure proxies for welfare under our definition. I am not going to impose a specific definition, but I'll assert that "people not wishing to kill themselves" correlates with a wide variety of plausible conceptions of welfare, so the suicide rate might be a proxy, no doubt dirty and imperfect, for diswelfare.

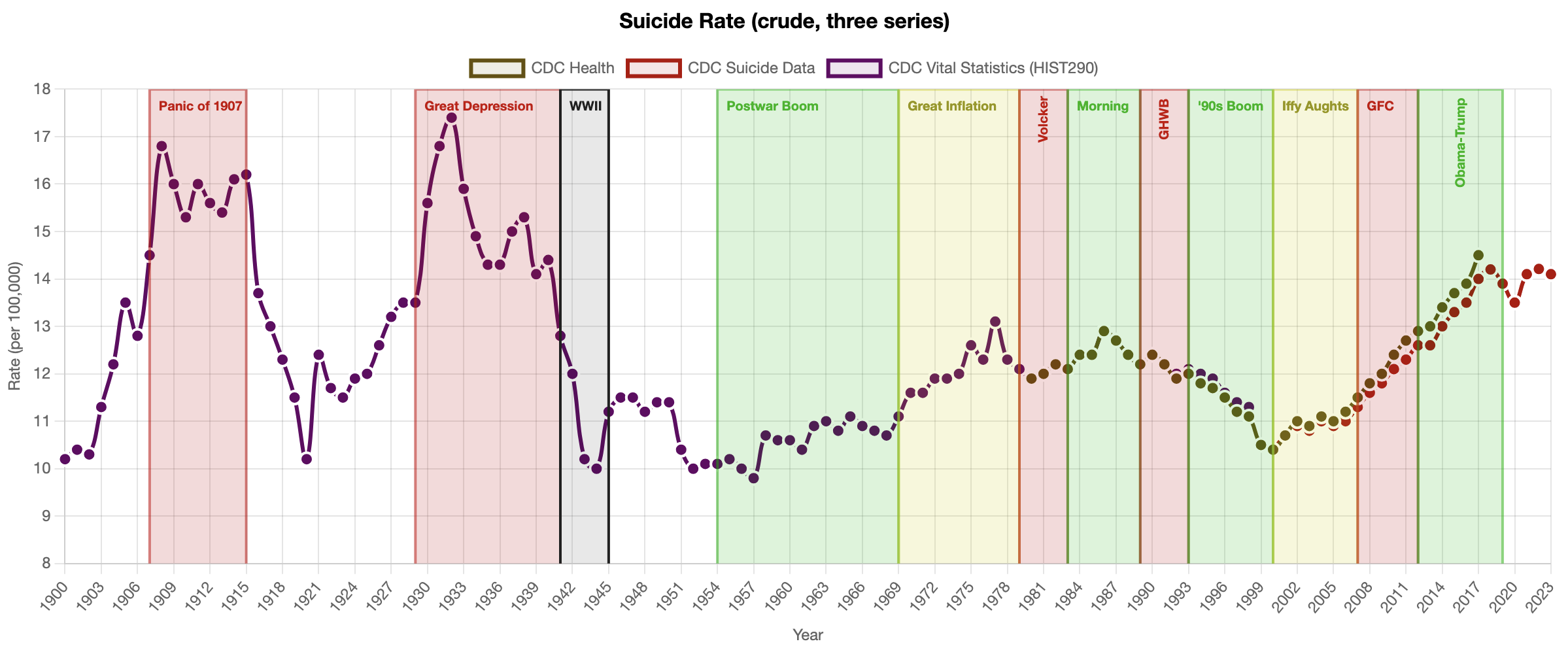

Here's a chart:

One thing that's fairly obvious is that the suicide rate does in fact have a pretty strong relationship with things we consider "economic". Both the Panic of 1907 and the Great Depression are very visible on the chart.2

I've included on this chart all the periods we teased out of the real median family income chart above, and bounded them with the same dates. I think that the two charts complement one another. In our earlier discussion, classifying the Great Inflation as a "meh" rather than "bad" period seemed wrong. We see a sharp rise in the suicide rate during the period, which suggests that "meh" should be bad. The suicide rate during the "iffy aughts" is much more restrained, suggesting a more benign period, as I think we mostly remember it.

There's a surprising spike in the suicide rate during the "Morning in America" period. I don't have an explanation for, or a story to tell, about that. I am eager entertain yours!

But for the period following, I think layering the suicide data on top of the purchasing power data helps us reconcile the numbers with our intuition. On the real median family income chart, the George-HW-Bush-era recession is an event comparable to the Volcker Shock and Great Financial Crisis. Those of use who lived through these events know that's wrong, the early 1990s recession wasn't fun, but it was a milder downturn than what the nation had gone through a decade earlier, and would go through nearly two decades later.

The suicide rate tells this tale: It rises during the Volcker Shock and rises sharply in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis. It is declining during the GHWB recession.

The suicide rate data also helps us reconcile discrepancies surrounding the late 1990s boom and the Obama-Trump expansion. My dark view of the Obama-Trump period may be idiosyncratic, but I think nearly all observers would agree that the late 1990s expansion was a bigger boom, a better economy, than the late 2010s. We see the suicide rate decline quite sharply during the late 1990s boom. It rises through most of the Obama-Trump expansion.

In general, there has been a strong upward trend in the suicide rate since the Great Financial Crisis, corresponding I think with the sense of upheaval and malaise also visible in social instability and the rise of outsider political movements. There's a kind of dark matter. Something is amiss, something is wrong that more conventional economic measures aren't capturing.

Perhaps the explanation is something not conventionally economic, negativity bias in social media for example. After all, social media and smartphones become prominent at approximately the same time as the Great Financial Crisis, so maybe they are the cause of the deadly gloom.

That is not my view. Long-time readers will know that I think our secular decline in welfare is related to the bifurcating class structure of American society and the unfairness implicit in how it must be sustained. In my view, the Great Financial Crisis both exacerbated these class divides and unmasked them, made them impossible to paper-over as we had managed previously.

I could be wrong! Maybe it really is just down to social media.

All I'll say is whatever it is, if there's a widely distributed product that makes us want to destroy one another and kill ourselves, that strikes me as very much an economic problem, an object that demands economic regulation. "Tech" is a big part of our economy!

Economics is either a positive science of predicting human behavior (in which case it has nothing to say about policy, except to inform other people who decide what we want), or it is a normative enterprise and its object is human welfare. If you are an economist and you say we should do X or Y or Z because it would increase GDP, but you have no reason to think the increase in GDP will make us better rather than worse off other than loose historical correlations, then you are much worse than useless. If it is plausible to you that big chunks of our economy are products so harmful they amount to half a Great Depression in suicide rates, then "maximizing GDP" cannot be a remotely decent proxy for the human welfare that it is your vocation to improve.

-

If I hadn't cheated at all, if I'd just placed boundaries at sharp turning points, the main difference would be taking the Postwar Boom as continuing through 1973, and then a shorter Great Inflation. The Volcker Shock would have been one year shorter, Morning in America one year longer.

↩ -

I marked the Great Depression as beginning in 1929, and ending in 1941, when the US joins the war. The Panic of 1907 begins in 1907, and I take its ending to be 1915, the last year of high unemployment. For more on the relationship between suicide rates and the business cycle, see Luo, Florence, Quispe-Agnoli, Ouyang, and Crosby. The suicide rate chart is a composite of three data sets, stitched together to cover the period, CDC Health, CDC (recent) Suicide Data, and CDC HIST290. Crude rather than age-adjusted measures are shown. Age-adjustment seems not to alter the qualitative picture. I want to thank Matt Darling for first showing me suicide rate data from 1900, further peaking my curiosity, and the late, irreplaceable Kevin Drum, who put together the chart Matt posted.

↩

2025-12-08 @ 02:45 PM EST