Why has the stock market been so ebullient?

Even by very forgiving measures like price-to-earnings, which presupposes extraordinary profit margins will be permanent, stocks are overvalued.

The question is academic to me now. The recent rally has wiped me out, replacing my short position with a shirtless one. Still, why does valuation seem more definitively and durably than ever before simply not to matter?

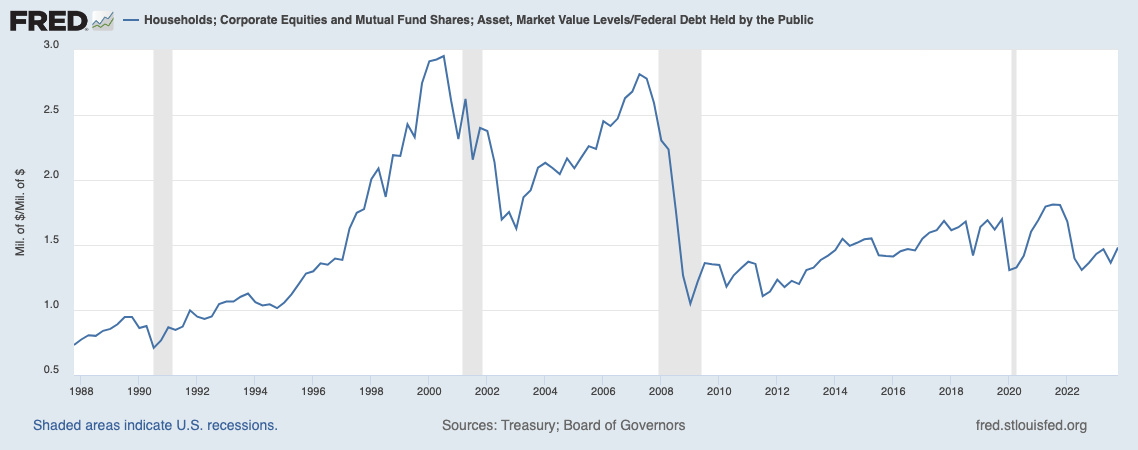

I present for your consideration a graph:

The denominator here is "Federal Debt Held By The Public", which is a good measure of US government paper issued, whether as US Treasuries directly, or as Treasury debt transformed by the Fed into bank reserves or currency. ("The public" in this measure includes the Federal Reserve, but the Federal Reserve's holdings of government debt are transformed into currency and reserves in the hands of the non-government public.)

The numerator is the market value of corporate equities, held directly or via mutual funds, held by US households.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, this ratio has stayed approximately constant. Basically, the total value of corporate equities gravitates around 1.4 times the quantity of Federal paper held by the public.

This is quite different from the prior era, during which this ratio fluctuated widely.

My explanation for this is very simple. Prior to 2008, equity holders as a class were engaging in speculations — or investments if you prefer — based volatile expectations surrounding corporate cash flows. There were periods of optimism (the late 1990s tech boom, the "democratization of credit" era that preceded the 2008 crisis), and periods of relative pessimism about corporate fortunes, all of which had little to do with the Federal government's debt position.

2008 began an era of asset-allocation dominance. Equity holders, as a class, are no longer engaged in speculations — or investments if you prefer — in cash flow outcomes. They had been taught, for at least a decade by 2008, that evaluating cash flows like a classic investor is a mug's game. Since stocks are riskier than other securities, some natural law of the universe would always ensure they eventually return more than anything else. Old-fashioned ideas like "valuation" could only mislead investors into foolish exercises like market timing. Just think of equities writ large as an asset that will always yield higher returns than other asset classes, at the cost that you must tolerate greater fluctuations in value. Then divide your wealth between this "risky" class and other assets — like cash and bonds — in order to titrate your risk and maintain a cushion in case you need liquidity during one of the bad fluctuations.

Obviously, asset-holders are heterogeneous, and not everybody behaves this way. People still do speculate on individual companies, evaluate growth prospects and cash flows, all of that. Relative performance within the broad class of equities still reflects expectations of firm-level analysts.

But in aggregate, the public simply seeks a portfolio with a ratio of $1.40 of diversified equity for every $1 it holds of goverment paper, treating the precise composition of the equity as a secondary question.

The price of government paper is largely pinned. There is some play in longer-term bonds, where investor behavior can muck with the term premium a bit, but for the most part, the value of government paper is set by face value, duration, and expectations surrounding the Fed. The price of equities, on the other hand, fluctuates freely.

So what happens is pretty simple. Suppose we start at "equilibrium", investors hold $1.40 of equity for every $1 of US paper. Suddenly, the government spends some money, or just pays interest on its existing debt.

Now the aggregate investment community is out of equilibrium. Cash (which, for our purposes, is just Federal paper in any form) is now a "hot potato", in the traditional metaphor. People have too much government paper, which they try to exchange for equities, but that just creates a hot potato in someone else's hands, unless and until the phrenetic equity-seeking bids up the price of existing equity in proportion to the new injection of government paper. Investors want their $1.4 in equities for every $1 of US paper. To a first approximation, the only thing that can adjust is the price of equities. So it does.

The behavior that drives this — valuation independent "investment" into "diversified equities" as a black-box asset class — enjoys a great deal of elite-intellectual and policy support. It is what good upstanding prosperous professionals are told they are supposed to do with their savings. Once upon a time, equity investing was understood to be a high information, potentially quite dangerous activity that a relatively small fraction of the public would engage in. Now, among prosperous professionals, failing to be long equities is a mark of laziness, stupidity, or some form of financial dissidence. Being invested in equities "blindly" — by which I mean without picking stocks or using valuation to time exposure — is what conventional, smart, politically enfranchised people do.

Inevitably, a policy apparatus evolves to stabilize whatever conventional, smart, politically enfranchised people do. Post-crisis, the Obama administration openly gauged the quality of the plans it would have Tim Geithner announce by the reaction of the stock market in the days following. Trump crowed about his stock market and autographed ascending charts that he thought he could take credit for. There has long been perceived to be a "Fed put". Economists like Roger Farmer have made stabilizing an ascending equity price path ever more acceptable in policy circles.

Valuation-independent investor behavior forms a Nash equilibrium around equity price expectations, in the same way and by the same dynamics as cryptocurrency booms. Unlike cryptocurrency, for equities the equilibrium is also stabilized by a wide variety of policy actors and instruments. Disproportonately enfranchised affluent professionals — call them the "top 30%" — are equity holders who have come to rely upon high equity returns regardless of the timing or valuation of their purchases. Equities fluctuate, sometimes wildly, but the most enfranchised citizens now expect an upward ratchet over a five to ten year horizon. Speculators' own self-fulfilling behavior joins forces with tacit but determined state support to deliver on that expectation.

As a normative matter, we'd be better off if "equities" were just some arbitrary token or cryptocurrency. Perhaps the state could offer EquityCoin in fixed quantity, or with some precommitted, demand-independent, issuance path. Wise men and talking heads could encourage conventional professionals to divide their wealth between government paper and holdings of EquityCoin, rather than buying actual corporate equities.

People like to imagine that by purchasing corporate equity, they are "investing" in the economy, allocating capital, making resources available to enhance future production of the goods and services that make us all prosperous. But bidding up the prices of existing corporate equities mostly does nothing like this. To a certain degree, okay. As share prices grow, firms are able to compensate employees cash-cheaply with options. They can borrow to finance new projects more easily. They can acquire conservatively valued private firms in exchange for just a few of their own overpriced shares. Firms do find circuitous means to take advantage of high stock prices, so, in very limited ways, mere share price appreciation can contribute to production.

But as long as there remains some pretense — however tenuous or residual — that equity prices represent capitalizations of future cash flows, high share prices also impose costs and obligations on firms that may be socially counterproductive. To support share prices, firms repurchase their own expensive stock, which drains companies of cash, and concentrates losses on long-term shareholders should valuations ever revert. Even if equity prices in aggregate are continually growing, at individual firms, managers struggle desperately to maintain the ratchet, to ensure whatever today's share price is, tomorrow's should be higher. Or at the very least — God help us — no lower.

I have argued before that we should think of "greed" as something structural, institutional, rather than an innate, individual characteristic. High share prices render firms insecure and rapacious as managers seek to ratify and support nosebleed prices with actual cash flows. When current profits comfortably justify their share price, managers might be content to grow by expanding quantity-produced at existing margins. But when the share price they must defend is not so justified, the pressure for profit growth may compel the same human managers to aggressively seek means of gaining market power and expanding margins at the expense of customers, vendors, and workers.

High share valuations are both a cause and effect of our terribly unequal, greed-inducing, Matthew-effect-ridden social arrangements. They are an ethical catastrophe. We should not want them, but it is hard for people whose 401(k)s are long the S&P 500 to want to see them to disappear.

Equity-invested affluent professionals tend stereotypically to be "fiscally conservative". If the dynamic I conjecture above is correct, well, careful what you wish for.

Share prices and government deficits are connected conventionally via the Levy-Kalecki profit equation. (ht Nathan Tankus) But that effect produces no expansion of valuation: share prices grow because profits grow. The dynamic described here leaves deficits not only padding corporate profits, but also supercharging multiples, whenever government debt is growing faster than earnings. Deficit restraint would both impair corporate cash flows, and reduce cash injections that investors now rely upon to deliver share price increases via portfolio composition effects.

One puzzle (to me at least) has been why high share valuations have been so resilient as we've transitioned from near-zero interest rates to short-term rates above 5%. I had, calamitously, expected share prices would not be so resilient. But if portfolio composition trumps valuation, then we should expect high interest rates to be good for share prices over the long run, despite short-term declines when raises are first announced. Interest rate cuts, by reducing fiscal injections, should be bad for stock prices over time, despite price spikes when markets first anticipate them.

David Andolfatto has recently pointed out that the short-run and long-run effects of interest rate changes can be quite distinct. Perhaps ex ante the stock market reacts through a zombie reflex discounted-cash-flow valuation channel, but ex post, once the cash actually flows — or does not! — the aggregate investor's thirst to conjure its desired asset allocation wins out.

2024-03-20 @ 02:35 PM EDT