Price regulation is in the ether. I find the "debate", such as it is, stupid. Some forms of price regulation, under some circumstances, can be helpful or even necessary. Badly crafted or misapplied price regulation can indeed lead to gluts, shortage, mangled incentives, and destructive allocations. It really does depend.

If you already know whether you like a "ban on price gouging" without having seen the details of the proposal, you are just an ideologue, one way or the other. If you hold yourself out as an economist and you are taking a strong position on the proposal at its current level of unspecificity, might I recommend my recent piece on authority minimization?

Rather than get ahead of ourselves, let's discuss a form of price reform that is occurring already, without any impetus from the state. The American Prospect recently did a full, remarkable issue on pricing, emphasizing price discrimination or "personalized pricing".

I find it a bit counterintuitive that it's my friends at The American Prospect who get upset about this, rather than my friends at George Mason University. (With genuine affection, I consider GMU Economics to be the lightbearer for Hayekian economics, now that the man himself has left us.)

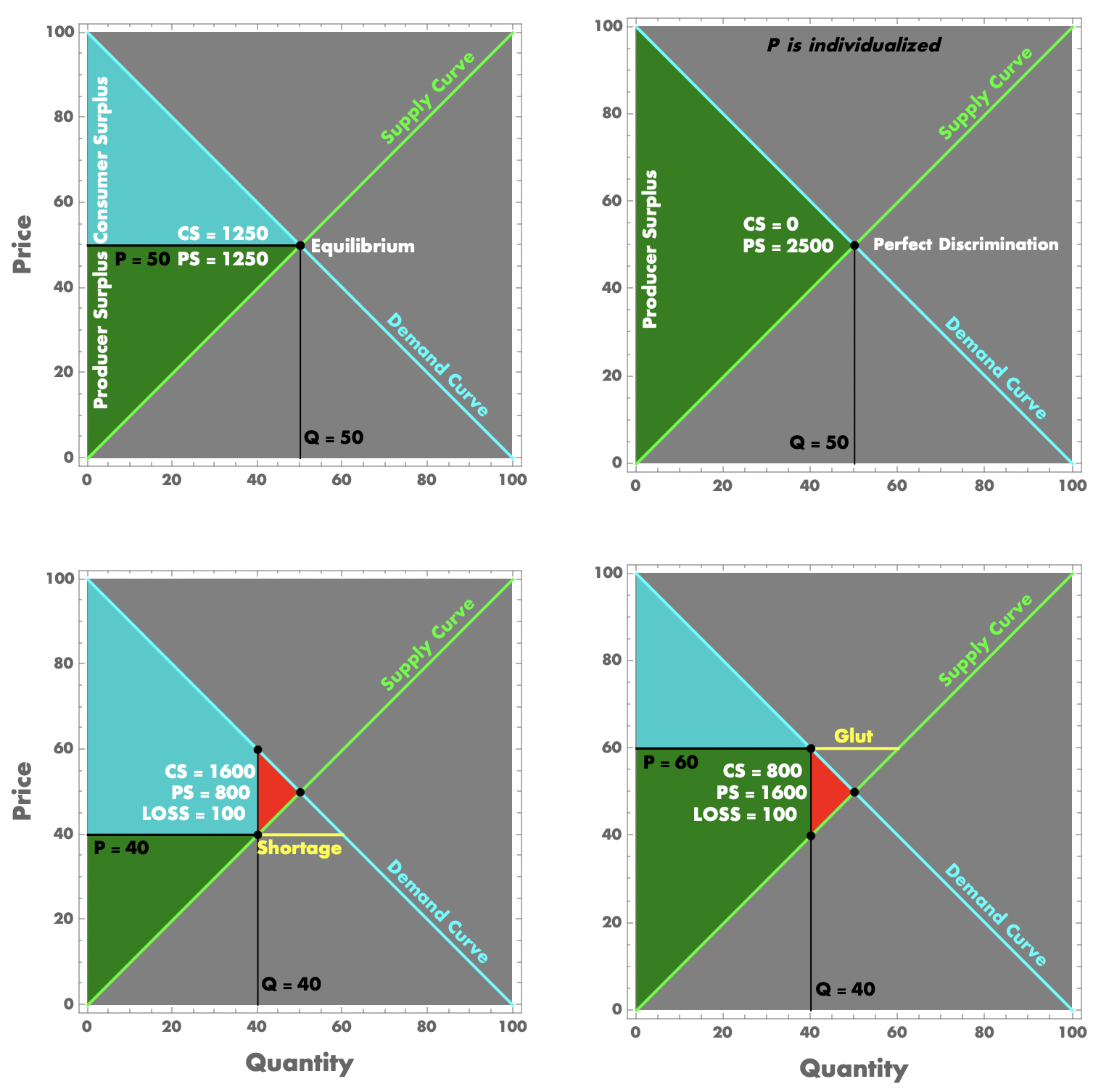

A common apology for first degree price discrimination is that it's "efficient". And it is, in one narrow sense. Let's review the Econ-101-style diagrams below (modified from an old piece):

The upper-left-hand diagram shows the Marshallian equilibrium that we ordinarily imagine as efficient. When the price — there is just one price, the same public price for everyone — has groped to where the supply and demand curves meet, both the quantity exchanged and total surplus is maximized.

The bottom row shows two pathological cases. If the price is prevented from finding the equilibrium price — whether by private market power or by public regulation — there is "deadweight loss" (the red triangles). Total surplus is reduced.

Surplus is a problematic measure of welfare, but Econ 101 courses disgracefully treat the two as interchangeable, so the smarty-pants pundit class does the same. Under this analysis, price-setting, whether by states or by monopolies, makes the collective "us" prima facie worse off.

The diagram on the upper right depicts "perfect" or "first degree" price discrimination. That's when sellers know precisely the maximum amount each potential customer would be willing to pay for an item, and charges precisely that. No real-life seller can know preferences so perfectly, but digital tools now surveil, study, cluster, and predict our behavior pretty well. In an app, on a website, even in a grocery store, pricing can increasingly be tailored to us.

Notice that in this diagram there are no scary red triangles, there is no deadweight loss. The quantity exchanged and the total surplus are the same as at the Marshallian equilibrium. So first-degree price discrimination is "efficient".

The difference from the competitive equilibrium (upper-left) is only distributional: In the single-price, Marshallian case, consumers and producers split the surplus. In the price-discrimination case, producers enjoy all the surplus, and consumers enjoy none. The purchases are "worth it" to buyers, but just. Whatever consumers have bought is worth barely more to them than the dollars they have spent. Sellers, on the other hand, receive a lot more money than it cost to market the good.

To a certain kind of economist, distribution doesn't matter, or is a second-order concern. That is far from my own view. People "on the left" tend to dislike price discrimination, because producer surplus (business profit) goes disproportionately to the already wealthy, while consumer surplus would have been more broadly distributed.

If you are Hayekian, you should have a different but equally fatal concern.

From Hayek's The Use of Knowledge in Society:

[T]he economic problem of society is mainly one of rapid adaptation to changes in the particular circumstances of time and place... [T]he ultimate decisions must be left to the people who are familiar with these circumstances, who know directly of the relevant changes and of the resources immediately available to meet them... But the “man on the spot” cannot decide solely on the basis of his limited but intimate knowledge of the facts of his immediate surroundings. There still remains the problem of communicating to him such further information as he needs to fit his decisions into the whole pattern of changes of the larger economic system...

[T]his problem can be solved, and in fact is being solved, by the price system...

[I]n a system in which the knowledge of the relevant facts is dispersed among many people, prices can act to coördinate the separate actions of different people in the same way as subjective values help the individual to coördinate the parts of his plan. It is worth contemplating for a moment a very simple and commonplace instance of the action of the price system to see what precisely it accomplishes. Assume that somewhere in the world a new opportunity for the use of some raw material, say, tin, has arisen, or that one of the sources of supply of tin has been eliminated. It does not matter for our purpose — and it is very significant that it does not matter — which of these two causes has made tin more scarce. All that the users of tin need to know is that some of the tin they used to consume is now more profitably employed elsewhere and that, in consequence, they must economize tin... The mere fact that there is one price for any commodity — or rather that local prices are connected in a manner determined by the cost of transport, etc. — brings about the solution which (it is just conceptually possible) might have been arrived at by one single mind possessing all the information which is in fact dispersed among all the people involved in the process.

(Emphasis mine.)

Let's consider a concrete case. I need a new roof, which could be made of tin or plastic. I prefer tin. I'd be willing to pay up to $9000 for a tin roof and $5000 for a plastic roof. A price discriminating monopolist offers me precisely those prices. Which I choose is then a flip of the coin. I've been deprived of information that might distinguish them. At these prices, I'm indifferent between the two options, or even to not buying at all.

Suppose that under a competitive single-price equilibrium, the tin roof would have cost $6000, and the plastic roof would have cost $1000. Because tin is dear relative to my own knowledge of my preferences (my surplus for tin would be $3000, for plastic $4000), I would have economized and purchased plastic, contributing to an efficient allocation. But under perfect price discrimination, my contribution to the as-if "single mind possessing all the information" is reduced to noise, a fifty-fifty coin flip.

Ah! you say, But the price discriminating seller wouldn't behave this way! Megacorp would know the "true" prices of underlying commodities, and would profit more from offering the plastic roof for $4900. At this price, I reliably choose plastic, the seller makes $3900 rather than the mere $3000 it would have made from tin, and tin is economized as it would be in a competitive market.

But then what you are saying is Megacorp's knowledge is sufficient to completely cut me out of the information aggregation process with no loss. My local information has no role to play. Megacorp knows me well enough to prejudge me and perform my role.

And maybe so! I don't know very much.

But it's turtles all the way down. If cartel and price discrimination are normalized, then Megacorp's vendors are also predicting what Megacorp will pay, and providing prices that maximize its own profits rather than reflect underlying social costs. Megacorp is also cut out of any role in the information problem. The system ultimately works — correctly solves the market optimization problem — only if there is some foundational set of vendors, a cartel for whom Hayek's "dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge" have been surveilled and aggregated and reconciled after all.

Long ago I tweeted

path to socialism: Amazon solves economic calculation problem and swallows the whole economy. then we nationalize it.

If you think an economy in which price discrimination is normalized can be efficient, then you think Hayek's work is obsolete. The cartel that price discriminates constitutes a capable central planner. If we will have a capable central planner, most of us would have it under the control of an imperfectly democratic state, rather than operate as a maximizer of private shareholders' wealth.

I do not in fact think Hayek is obsolete. Neither Amazon nor ChatGPT can incorporate the ever-changing, infintely dispersed knowledge that drove Hayek's vision.

But if Hayek is not obsolete, if we move towards "personalized pricing", firms will routinely price discriminate but misjudge. On the one hand, that means at least sometimes consumers will still enjoy surplus. Hooray!

At the systemic level, however, it means our optimizer will be badly broken, and we will all be made the poorer. Megacorp will think I'd be willing to pay $6000 for a plastic roof, and so offer it to me for $5900. But for that price, I prefer the tin. A social resource will have been diverted from a high-value to a low-value use, because our price-discriminating planner erred. Multiply this kind of mistake countless times, and Hayek's “economic calculus” goes haywire. We will have destroyed the very purpose and function of markets in our economy.

Either price discrimination can be perfected, and we should move to a centrally planned economy. Or it cannot be, Hayek remains right, and we should insist on competitive markets with single public prices. Which is it?

"I have deliberately used the word 'marvel' to shock the reader out of the complacency with which we often take the working of this mechanism for granted," Hayek writes of the price system.

I find it astonishing how untroubled Hayek's successors now seem by developments that could only be wise if Hayek's marvel has become a museum piece.

Maybe AI really will do a better job of allocating scarce resources than markets and the price system used to. Maybe it really is time to move on.

But you'd think Hayekians would be evaluating that claim skeptically, rather than cheerleading the change.

2024-08-18 @ 08:00 PM EDT