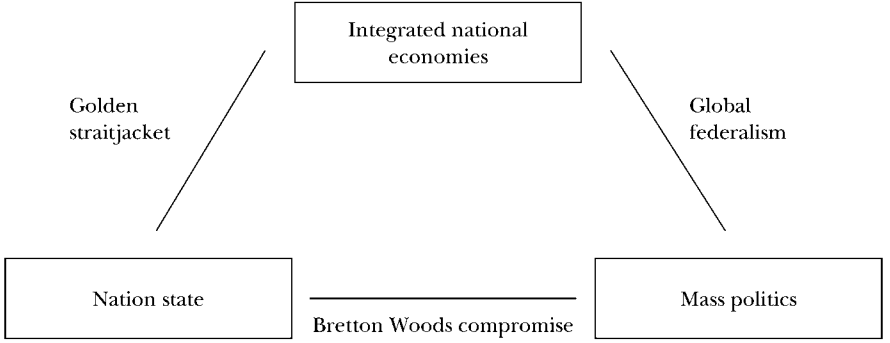

In 2000, Dani Rodrik proposed the "political trilemma of the world economy":

Rodrik argued that the world would have to choose only two out of three between "international economic integration, the nation-state, and mass politics". By mass politics, Rodrik means meaningful and effective democratic control.

We can choose economic integration and mass politics, if we give up political control at the nation-state level. Rodrik calls this "global federalism", effectively global governance in the mold of the United States. Subsidiary states still exist and matter to a degree. But regulation of interstate commerce gets hoovered to the highest level. And in an interconnected world, nearly all commerce, nearly all production and consumption, must be regulated as interstate commerce. Even transactions that are purely local are conditioned by and in turn affect larger markets.

We can choose economic integration and preservation of distinct nation-states, if we give up on meaningful democracy. Under this scenario, which Rodrik — after Thomas Friedman — calls the "golden straitjacket", distinct nation-states continue to exist, but international markets impose ever increasing constraints on their political choices. In Margaret Thatcher's infamous words "There Is No Alternative" to a narrow range of policies, if a country is to participate and compete successfully in global markets. In order to prevent catastrophe, nation-states become compelled to remove ever larger swathes of policy out from democratic contestation, into the remit of unaccountable technocracies like central banks and treaty organzations. As former German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble famously put it, "Elections cannot be allowed to change economic policy."

Finally, we can choose the nation-state and meaningful democracy, if we give up economic integration. Each nation-state can captain its own ship, regulate its own affairs if those affairs are neither subject to constraints from, nor responsible for dangerous spillovers to, highly integrated trading partners.

Rodrik called this last choice "Bretton Woods compromise", which is a clue that his trilemma is maybe a bit less sharply drawn than "pick two out of three". Economic choices are rarely binary. "International economic integration" is an umbrella term for many dimensions of policy, most of which are subject to lots of choices between all or none. Imports can be forbidden, or they can be permitted with tariffs. In the latter case, very high tariff rates would correspond to isolation, very low rates would be consistent with integration, and levels in between embody a kind of compromise. The postwar Bretton-Woods-era, as Rodrik describes it, was a pick-two-and-a-half out of three scenario. The period from 1945 until the early 1970s was a period of extensive and growing world trade. But it was also a period of fixed exchange rates, capital controls, and insulation of certain industries from global competition by tariff.

Rodrik, writing in optimistic Y2K, predicted eventually we'd find our way to global federalism, under which the whole world could enjoy the prosperity that universal trade and specialization might bring, while an enfranchised global public could ensure that this fantastic global market would remain embedded in society rather than become a monster lording over it. To his credit, he did not predict this would happen very soon, and suggested that twenty years from when he wrote, financial crises might force the world into a "golden straitjacket", or else backlash might provoke global disintegration via a protectionist backlash. Twenty five years later, we can observe that both of these predictions came true, one in quick succession to the other.

And so here we are. The place where we are would have been familiar to John Maynard Keynes. Like those of us of a certain age, he grew up in an era when economic liberalization and trade seemed poised to deliver remarkable prosperity, only to watch it all give way to war and protectionism.

I want to rescue "nation-state ⇔ mass politics" side of the Rodrik's triangle from the historical particulars of Bretton Woods, both the conference and the institutions it wrought. So I'm going to refer to this really two-and-a-half out of three arrangement, with nation-states, meaningful democratic politics, and moderate rather than complete economic integration, as the "Keynesian compromise".

In 1933, Keynes had drawn the lesson that

Ideas, knowledge, science, hospitality, travel these are the things which should of their nature be international. But let goods be homespun whenever it is reasonably and conveniently possible, and, above all, let finance be primarily national.

However, by 1944, the system Keynes helped architect at Bretton Woods, and even the system he had more idealistically proposed previously, were quite open to foreign trade. The Bretton Woods order, at its inception at least, did retain some of Keynes' earlier skepticism of globalized finance. Capital controls were explicitly permitted, and countries were permitted to modify their otherwise fixed exchange rates to redress unbalanced trade.

To redress unbalanced trade. That was the fundamental work of the Bretton Woods order, of the Keynesian compromise. Keynes lived from 1883 to 1946, and to me the takeaway from that period of time, and from Keynes' interventions into international economics, is a kind of biohazard symbol, something very creepy. Call it "Econohazard". Affix it to a box secured with seven seals, cabining imbalance of trade, along with international indebtedness by other means.

Trade is supposed to be win-win. Both parties benefit. But persistently unbalanced trade has this strange effect of turning parties on both sides of the imbalance into self-perceived losers, into victims.

Surplus countries — think Germany with respect to Greece during the 2010s Eurocrisis — perceive themselves as prudent and generous, as innocents betrayed and sinned against when, inevitably, deficit countries suffer crises, and seek to devalue or default upon obligations that surplus countries accumulated in exchange for laboriously produced goods and services.

Deficit countries perceive themselves as having been led down a primrose path by eager sellers, then drained of both their financial net worth and their vigor. They are left emasculated, enervated, bereft of lost ability and capability to compete. Angry.

Both parties have a point. But then, of both parties, it is rather an infantile point. No one forces a trade surplus country to sell goods and services for potentially dodgy financial claims. No one forces a trade deficit country to borrow, or to tolerate borrowing by its public, in order to import goods and services.

No one forces these things. But countries may have been, if not forced, then strongly encouraged, to overlook imbalance by Rodrik's "golden handcuffs" regime, under which the price of economic integration becomes accepting free flows of both goods and capital. In my view, after the world abandoned Bretton Woods, it drifted toward an order — pick your pejorative, "neoliberal", "Washington Consensus" — that effectively required countries to abstain from tools by which they might have enforced trade balance.

It is perhaps ironic, perhaps you think it poetic justice, that the country usually seen as cheerleader of this consensus is now blowing up its own economy and hegemony via less-than-deliberate reaction to the consequences of what it advocated. The American partisan I still harbor will object and point out that the architects of the EU were every bit as blind and foolish. One thing you can say for Western elites on both sides of the Atlantic during this period from, say, 1983 until quite recently, is they were sincere in their error. The medicine they prescribed to the global South they also guzzled down themselves. As Nayib Bukele might say, "Oopsie..."

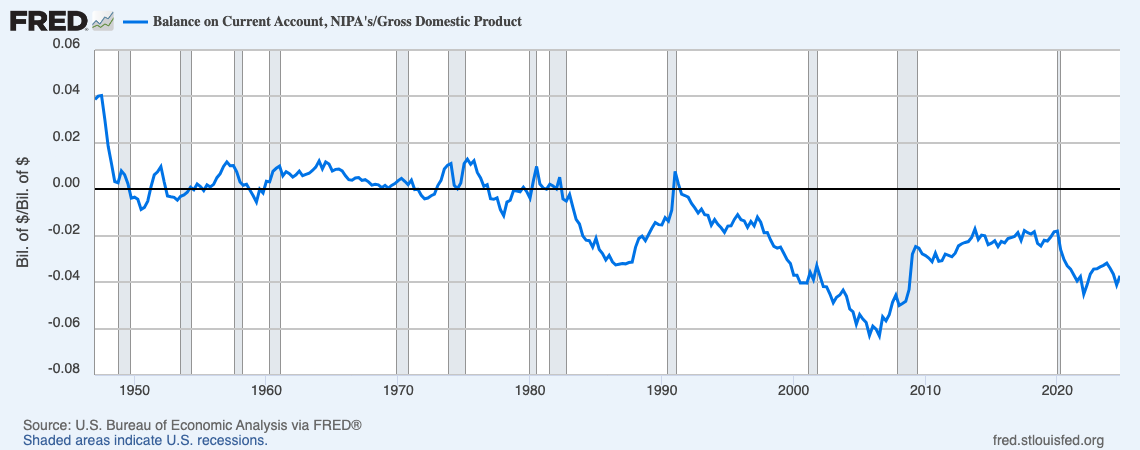

Here is the United States' balance of payments as a share of GDP, from the end of World War II to the present.

Despite the fact that, at the end of the war, the US was the only major industrial power whose factories had not been largely destroyed, by 1950, the US balance of payments is in balance, and it remains in rough balance through the early 1980s. Most of that period was good, economically, for the United States, and for its major trade partners. The institutions of the original "Bretton Woods compromise" are broken between 1971 and 1973 but the US endures and escapes its 1970s inflation while maintaining rough international balance.

One apology for neoliberal insouciance toward balance of payments is that unbalanced trade helped bring forth the greatest economic miracle in human history, the sudden, sharp rise of a billion plus Chinese out from acute poverty. Perhaps, but it's worth pointing out that Europe and Japan circa 1945 had become very poor, and their redevelopment from the ashes of war into prosperous social democracies did not require huge imbalances with trading partners. History is only run once. But it is not obvious that China could not have developed and succeeded with its market reforms in a world of balanced trade. If it had, the developed world that it joined might be more stable and peaceful than the one in which it finds itself now.

Perhaps Dani Rodrik was right back in Y2K, and by 2100, we'll all enjoy democratic enfranchisement in a prosperous, stable United Federation of Planet Earth. But for now, it seems to me the place that we want to go is back to Keynesian compromise, where we get two and a half out of Rodrik's three desiderata: nation-states, meaningful democracy, and economic integration.

It's that last bit, economic integration, that we only get half of. With Keynes, I say that the half we leave behind is cross-border finance. What we want is free but balanced trade. Tariffs are a tool poorly targeted to encouraging balance. Tariffs tax all trade, not just unbalanced trade. If instead you tax foreign payouts from securities, or otherwise deter cross-border accumulation of obligations, you can specifically disfavor imbalance.

If you insist upon balance and disfavor cross-border ownership, you restore scope for meaningful economic democracy, Rodrik's "mass politics". The neoliberal free-trade regime eroded democratic prerogatives primarily through its obsession with "non-tariff barriers". All kinds of government actions can affect trade or devalue foreigners' investments. Banning a dangerous chemical might constitute an "expropriation" from the multinational that manufactures it. An anti-smoking law might discourage imports and sales of Marlboros. "Sweatshop labor" is a non-tariff barrier from the perspective of nation-states that wish to offer strong labor protections. Joe Weisenthal points out, jokingly but accurately, that Europe's narrow streets disfavor US monster truck exports.

When countries compete mercantilistically for surpluses, non-tariff barriers are a big problem. The Trump administration's apocalyptic, now withdrawn, "reciprocal tariffs" were motivated in large part by accusations that bilateral surplus countries were "cheating" the US via non-tariff barriers. But under an overall balance constraint, to whatever degree non-tariff barriers discourage imports to a country, they also foreclose the possibility of exports. A country's regulatory environment can shape whether it is more or less integrated in world trade, but cannot be used drain other countries of tradables demand or to accumulate foreign financial claims.

If cross-border ownership is discouraged, multinational brands will prefer to license per-country franchises rather than directly hold property or plant. Then whatever "expropriation" is embedded in a regulatory change becomes a domestic political matter rather than predation of unfairly disenfranchised foreign concerns.

Of course, discouraging imbalance will not (and should not) yield perfect balance at all times. A trading regime that generally disfavors cross-border ownership doesn't mean it won't make sense sometimes for foreign owners to accept a penalty and invest directly, or for countries sometimes to seek and so affirmatively encourage foreign direct investment.

But it's the norms of the trading regime that matter. If our aspiration is a world in which capital is mobile and international ownership is the norm, then mechanisms like ISDS make sense. If we seek a world in which ownership is generally domestic, then they do not. If countries have the tools to unilaterally prevent trade deficits and a global consensus encourages balance, then running a deficit or surplus becomes an exception that demands justification. This sharply contrasts with the fading neoliberal view, under which imbalance reflects putatively optimal market outcomes, which deserve deference.

In my view, we are at the tail end of a half-century mistake. The Keynesian compromise — free trade, but subject to a balance constraint — was wise. We should return to it. If possible, we should rebuild it on an infrastructure of norms and tools that nation-states can unilaterally deploy to enforce those norms, rather than rely upon supranational institutions.

2025-04-20 @ 07:30 PM EDT

- Global Imbalances — Warren Buffett’s Cap & Trade

- Countering currency manipulation with high deficit spending

- Two Cheers for Bernanke’s Speech on Trade

- Fixing “global imbalances” in three easy steps

- Revaluing China

- China as a model

- If we weren't idiots, Balance of Payments edition

- Balance as a norm

- How can taxing foreign investors balance trade?

- Overall but not bilateral balance

- The asset side of the balance sheet