Interfluidity hosts office hours, Friday afternoons, 3:30 pm US Eastern time. These are open to all. Just drop-in here. Some brilliant people have become regulars. (Though I fear to jinx things by referring to them that way!) “Regulars" who I know have some public presence include Detroit Dan, Chris Peel, Everett Reed, Steve Roth. Other, less exhibitionist, regulars include M.A., T.A., and G.G. Attendance at these meetings does not imply endorsement of my bullshit. They all do their best to set me straight. But they do provoke me. A lot of what I write is inspired by their insight and conversation.

Last Friday, I held forth a bit on a very high-level story of the US macroeconomy, and Steve Roth suggested I write it up. So, here goes.

I divide the postwar era into six not-quite-disjoint eras:

- Treaty of Detroit (1950 - early 1970s)

- Baby boomers' inflation (1970s - early 1980s)

- Stumbling into the Great Moderation (1980s)

- Democratization of credit era (mid 1980s - 2008)

- Collapsing into Great Disillusionment (2008 - 2020)

- Capital as baby boomers and a new 1970s? (2021 - ?)

1. Treaty of Detroit (1950 - early 1970s)

Immediately postwar, we lived in a benign Keynesian technocracy. Aggregate supply was a function of accumulated fixed capital and continual productivity growth. Aggregate demand was a function of aggregate wages. Aggregate wages can be oversimplified as a conventional wage level times the size of the labor force.

During this period, aggregate supply was growing faster than the labor force. This meant something close to full employment — at a full conventional wage — could be accommodated without putting pressure on the price level.

Under these conditions, hydraulic Keynesian "fine tuning" could basically work. Technocrats could stabilize the price level and ensure full employment without provoking very difficult tradeoffs. Labor unions could insist on job security and wages that grew in real terms every year, to the vexation of the shareholding class, no doubt, but without creating macroeconomic difficulties.

This is not to say all was well and perfect. Between 1950 and 1970, the US experienced three relatively mild recessions. There was a significant inflation related to the Korean War in 1950-1951 , and, famously, a smaller, "transient" inflation in the mid 1950s. But this was turbulence in a booming economy, not failure of an economic regime.

By the late 1960s, there were adumbrations of what was soon to come. Inflation was picking up. The seeds of great misery were planted by Milton Friedman in a 1968 speech, introducing to the world the idea of a "natural rate of unemployment" beyond which there must be accelerating inflation. The 1970s would fertilize that soil, and by the 1980s those seeds would yield weeds so robust we have still not entirely shaken them.

2. Baby boomers' inflation (1970s - early 1980s)

I've written this up before, to some controversy at the time.

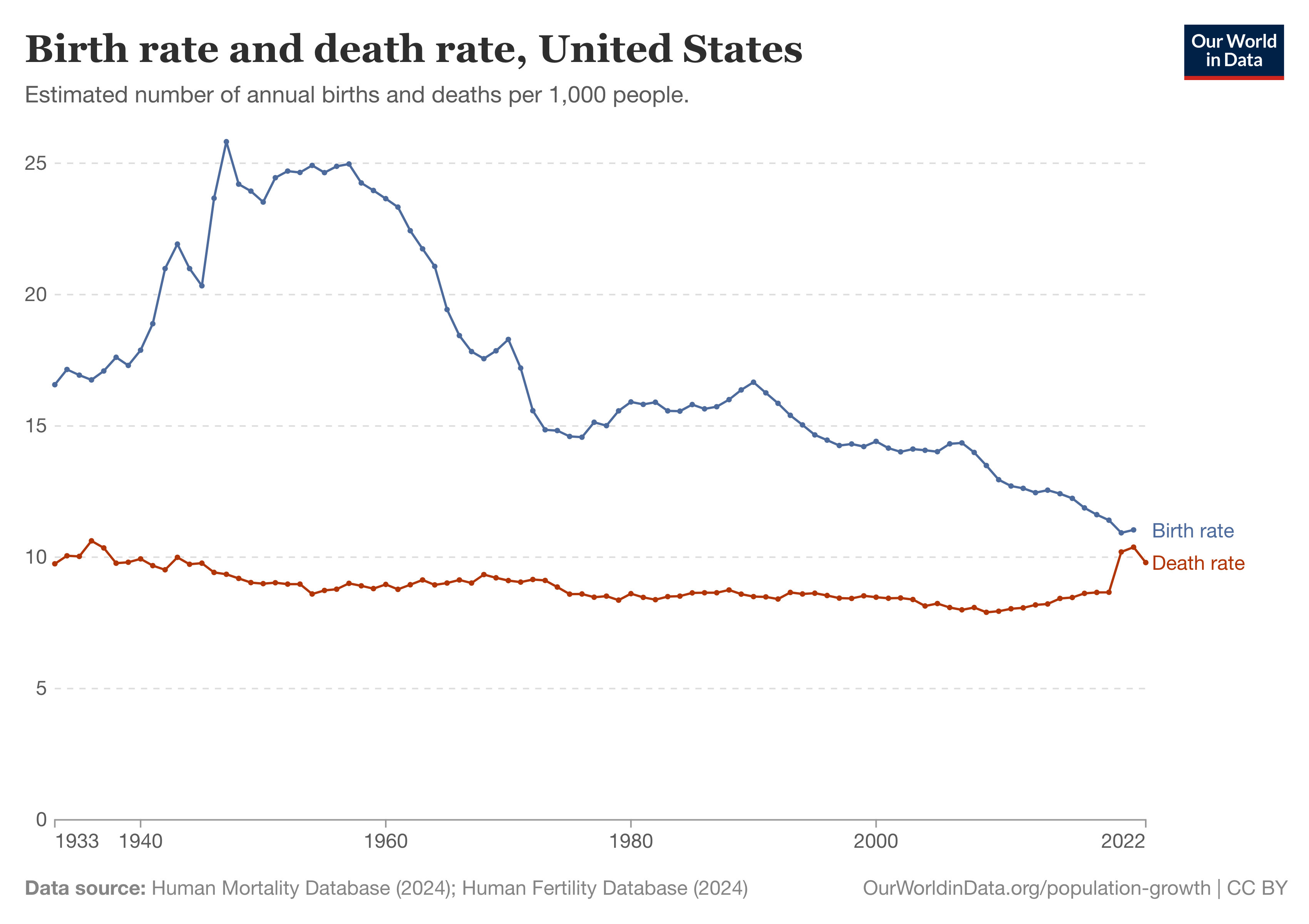

The postwar baby boom was an unpinned grenade, nonchalantly waiting to blow up the prior period of macroeconomic stability.

So long as the babies were babies, they were no problem. Sure, parents had to care for them, but since most working families had kids, the conventional standard of living included child-care costs. Workers on conventional wages didn't feel disadvataged or ill-done having to cover them. Society was arranged so that it was possible for conventional wage-earners to afford and raise children.

But once the kids grew up, when they too became workers and wanted to contribute, that's when they became a problem. Isn't it ironic.

Labor productivity is a function, at any given moment, of matching labor to the existing stock of capital. The US economy was accustomed to, and able to, develop new fixed capital fast enough to match a certain rate of influx of new workers into the labor force.

But the baby boom was a firehose that outstripped the pace at which the US could develop new fixed capital.

Further, young women of the baby boom generation joined the labor force at higher rates than prior generations, and expected pay closer to conventional male-worker wages. The US labor force suddenly faced a challenge of employing a lot of new entrants, and employing them productively enough to meet pretty high wage expectations.

But this firehose of new workers, unmatched to capital, could not be employed at the level of productivity that had been typical previously. The 1970s' infamous supply shocks exascerbated the productivity challenge. Still, the kids expected to earn a conventional wage in real terms, meaning, in the jargon (and the pronouns) of the day, a wage on which a person could afford his own pad and wheels and live independently.

An economist might predict that a sharp, sudden influx of workers that engendered a reduction of productivity of the marginal worker would lead to a decline in real wages. Or else to unemployment, if real wages are sticky or not permitted to decline.

For many of the United States' unionized workers, real wages were not permitted to decline, as a matter of contract. But a very energetic and entitled generation of young people, which only a few years earlier had somewhat credibly threatened revolution, were not going to tolerate unemployment.

Immovable object, irresistible force.

Policymakers were in a pickle.

Inflation was, if not exactly a solution, then a confusion that allowed the country to muddle through. The Great Inflation was miserable and unfair — it picked a lot of losers! — but precisely via its misery and unfairness, it helped address both the problem of unaffordable real wages and the problem of sustaining youth employment. In the unionized 1970s, some older workers were protected by COLA clauses in their contracts, others were not. Those who were not, and who otherwise had little bargaining power in their jobs, were handed very large real wage cuts. Not by any boss or politician they could get mad at, but by an inhuman demon, a "natural market force", a thing that economists and newsmen called "inflation".

By the end of the decade, real wage cuts to the unlucky were sufficiently deep to create space to employ the cohort of younger workers at their non-negotiable pad-and-wheels wage floor.

The net effect of the inflation was a real wage cut, on average. But it was concentrated among non-union, lower-bargaining power older workers, who were neither revolutionaries nor electorally organized, and so whose pain could be tolerated. It was also a redistribution from these workers to young new entrants, who were revolutionaries, or who might have been, had they not in this way been satisfied.

3. Stumbling into the Great Moderation (1980s)

The poor tradeoffs under which the Great Inflation had been the best of a lot of bad choices traumatized policymakers. At the same time, Americans made the catastrophic error of electing Ronald Reagan, who represented aggrieved capital, and who even under the prior, benign, macro regime would have sought to crush workers for the benefit of shareholders.

So crush workers for the benefit of shareholders they did!

It's easy to explain why Reagan and his political supporters tore to shreds what vestiges remained of the Treaty of Detroit. They represented business owners, a faction contesting with other factions for a greater share of output, which they were sure they deserved. Nothing is more ordinary.

But what's interesting is that well-meaning technocrats — and not only the ones bought off with lucrative sinecures — largely agreed that this was the right thing to do.

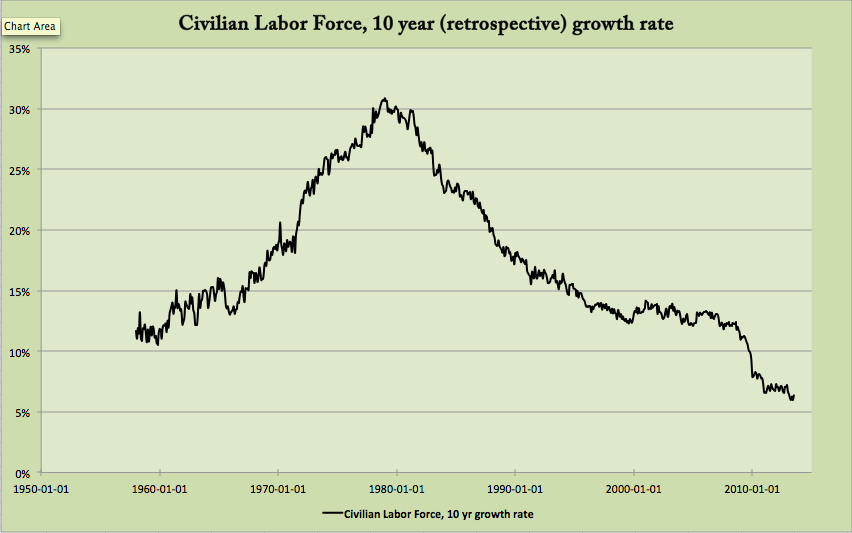

The 1970s had exposed a tremendous fragility in US macro- and political economic arrangements. Our ability to manage the price level and ensure something like full employment had proven dangerously coupled to vicissitudes of the labor force. In oversimplified, overaggregated Keynesian terms, the marginal dollar of aggregate demand — the expenditures that determine the price level, that decide the inflation rate — came out of nominal wages. And that was a problem.

While it is straightforward for policymakers to stimulate nominal wage growth, policymakers have no palatable tools to reduce nominal wages when there is an upward shock to the labor force or a downward shock to aggregate supply. In the United States (not everywhere!), reductions in labor demand provoke adjustments on the extrinsic rather than on the intrinsic margin. That's ugly economist-speak, but all it means is that, as the wage pool dies up, people get fired rather than everyone keeping their jobs at lower pay. In the US, when demand is tightly coupled to wages, the only way to restrain demand is to put people out of work and provoke a recession.

But then Reagan, for his own reasons, crushed the American labor movement. The wage share of the economy had declined as inflation reduced real wages over the course of the 1970s. It continued to decline over the disinflationary 1980s, thanks to Reagan's labor-hostile administration.

The American policy apparatus, whose job is to stabilize, almost automatically ensured that, when wage-financed demand faltered, alternative sources of demand would be stimulated to ensure the economy kept humming. The stock market boomed. Real estate boomed. That was "natural", you might say. As labor bargaining power declined, a greater share of revenues could be appropriated by their firm's residual claimants, shareholders. Wealthier people are real-estate buyers, and as more wealth flows to the rich, real-estate prices get bid.

Then asset price booms tend to bring with them borrowing booms — from speculators seeking leverage, from families borrowing to afford increasingly expensive homes, from owners of appreciating assets seeking liquidity in order to spend some of their windfall.

Policymakers quickly realized they were in a much better place. Before, the only way they could "fine-tune" economic activity downward was to reduce aggregate nominal wages, which would provoke unemployment, recession, political disquiet. But now the "marginal purchaser of a unit of CPI" was spending out of borrowings or capital income, rather than out of wages. Policymakers could downregulate these sources of demand much more painlessly. As before, policymakers would raise interest rates to prevent inflation. But now raising rates would exert their effect before very many people were thrown out of work, simply by reducing borrowing and blunting asset price growth.1

Economic policymakers had stumbled into "the Great Moderation", and they wanted to keep it. Although they hadn't predicted or engineered it, exactly, after the fact, they did understand how it worked. They had been cornered in the 1970s because their core policy objectives — full employment and inflation — were structurally in conflict, so long as the price level was very tightly coupled to nominal aggregate wages. By suppressing nominal aggregate wages and replacing the suppressed increment with borrowings and capital income, they decoupled employment from inflation. They could sustain "full employment" and modulate borrowings and capital income in order to achieve their policy objectives.

Note the scare quotes around "full employment". Policymakers understood that if they were going to keep this great achievement, they had to prevent any upsurge in labor bargaining power that might render adjustments to borrowing and asset prices insufficient to the task of containing inflation.

So they tended Milton Friedman's seeds. They redefined "full employment" to mean Friedman's "natural rate of unemployment" — or the much more technical-sounding NAIRU ("non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment"). They estimated it to be… about 6%! During the "Treaty of Detroit" era, 6% was a recessionary level of unemployment. By the early 1990s it had been recast not only as normal, but as a desirable, optimal.

The Federal Reserve remade itself into a kind of financialized union buster. Its role was to watch, eagle-eyed, for any sign of "wage pressure", for any upward creep of unit labor costs, and then threaten to bust up the economy if that strength was allowed to continue. Robust wages had cornered and embarrassed America's technocrats in the 1970s. That would not be permitted to happen again.

4. Democratization of credit era (mid 1980s - 2008)

The real innovation of the Great Moderation, as I described it above, was to suppress wage income and replace it with financially-sourced cash such that "the 'marginal purchaser of a unit of CPI' was spending out of borrowings or capital income, rather than out of wages".

This implies that, in some sense, a "typical" American lifestyle would no longer be affordable on wages alone. The prototypical purchaser of the CPI bundle earned wages, sure, but supplemented those wages with either capital income or borrowings. The typical wage earner would not be able to afford a typical level of consumption only out of wages.

That sounds pretty bad! Then as now, most people are not wealthy enough to earn meaningful financial income.

You need wealth to earn capital income. But you don't have to be rich to borrow. Anyone can do that, as long as they can find a willing lender.

The Great Moderation macro regime might have been politically untenable, as the great bulk of the public would find their capacity to consume out of wages diminished relative to an average level of consumption set by the asset-owning rich.

That's not what happened. Instead the broad public kept up with the affluent Joneses by borrowing to supplement their consumption. Often they borrowed against rising home values, against the collateral of unrealized capital income. (In some cases this income never would be realized, after it disappeared during the 2008 financial crisis.) Uncollateralized credit card borrowing also exploded during this period. Credit really got democratized during the early 2000s when origination fraud and NINJA loans were added to the mix.

In 1995, Lawrence Lindsey coined the term "democratization of credit", in order to answer the question "Where are consumers getting their money?":2

[T]wo key financial innovations have eased the liquidity constraints that households face… The first is the increased ease with which housing may be turned into collateral for a mortgage. The second is the incredible increase in the use of credit card and other installment debt… [U]nsecured consumer credit growth seems to be entering an unprecedented period… While all of this… may sound bleak, there is an important bright spot in the trends described here. One of the key points that has been overlooked by many commentators is the increased democratization of credit in America… Recent developments in housing finance… show a very large expansion of credit opportunities and therefore homeownership opportunities for traditionally underserved groups… I do not believe it is possible, however, to attribute anything approaching a majority of the current very expansive use of consumer credit to positive sociological factors… [G]rantors of consumer credit may now have collectively taken on a macroeconomic responsibility they did not seek. The evidence indicates that the old liquidity constraint which used to discipline household consumption behavior has been replaced by a new constraint -- the credit card limit.

At a very high level, the response of a motley alliance of plutocrats and technocrats to the trauma of the 1970s had been to make the rich richer and most of the public poorer. Plutocrats were for this because, of course. Technocrats did not favor the inequality per se, but they wanted to decouple macroeconomic management from politically inflexible wage income.

The majority of the public was made poorer than they would have been, and ought to have objected, but we mostly remember this period as good times. There was the late 1990s stock market boom, but most people did not substantially participate in that (and then there was the bust).

Instead, many households enjoyed growing consumption thanks to an increase in their ability to supplement their purchasing power with borrowing, which helped offset the loss of purchasing power they experienced from reduced real wage income.

Unfortunately, replacing wage income with borrowing at best renders household balance sheets more fragile (when, for example, households are borrowing against rising home values), and potentially drives households to outright insolvency (when they run up uncollateralized consumer debt). Chickens would eventually come home to roost.

5. Collapsing into Great Disillusionment (2008 - 2020)

The Great Financial Crisis happened. I won't go into it. Read my archives for my thoughts on that pain in real time.

For our purposes here, the Great Financial Crisis had two relevant effects. First, it killed the democratization of credit. Less well-off people could no longer borrow nearly as easily. Lots of people emerged from the crisis with damaged credit histories and would have difficulty borrowing at all. Second, it did not kill the Great-Moderation regime under which wage income would be suppressed in favor of capital income. It took 76 months for employment to recover from the 2008 downturn. It only took about 66 months for the S&P 500 to soar past its prior new peak. By the beginning of 2020, the S&P 500 had more than doubled from its prior peak — after paying dividends — while total labor compensation, in nominal terms, had grown only about 30%.

Despite (to their credit!) eventually tolerating unemployment levels way below 90s-style NAIRU estimates, economic policymakers found it difficult to sustain robust demand without the exuberant borrowing of the democratization-of-credit era. Only in early 2018, after a decade of underperformance, did US GDP reach estimates of potential GDP. From the end of 2008 to the end of 2015, the Fed's policy rate was stuck at the zero-lower bound, suggesting an economy policymakers understood to be starved for demand which conventional tools could not stimualte. Until 2014, the Fed expanded its balance sheet in a practice it called "quantitative easing", deploying an unconventional tool to make up for the missing demand. Policymakers relied on stimulating financial asset prices rather than, say, fiscal expenditures structured to help bid up wages. Despite all that had gone wrong and growing political turmoil, the Great Moderation "lesson" was not unlearned. Finance, rather than wages or transfers, remained the instrument of demand management.

We mostly remember the democratization-of-credit era as good times, a period of prosperity. Even though wage incomes were suppressed, we enjoyed a brisk economy and broad based consumption growth.

We do not remember the 2010s as good times. The 2010s is when we really felt the inequality that had been metastatizing in our economic statistics for decades. The financialized well-off in America somehow weathered the "financial" crisis and were rewarded with recovering, then booming, asset values. The less well-off simply afforded less. They "adjusted", in economists' deceptively bloodless term for suffering.

The Great Disillusionment gave us Donald Trump, the first time around, as a well-deserved but ill-chosen middle finger to the policy establishment that had walked us all along this path, to this place.

By the end of the decade, it was unclear whether the Great Moderation policy regime — wage suppression, financial stimulus to fill in the gap — might change. Wages underwhelmed, but that seemed to be despite rather than because of policymakers' efforts. The Fed tolerated low (by recent decade standards) unemployment in the late 2010s, as it had in the late 1990s. Inflation risks seemed very distant. We were consistently undershooting the Fed's informal 2% PCE inflation target. Policymakers did not foresee or fear an environment in which strong labor bargaining power might create difficult tradeoffs between inflation and unemployment. In public communications, they were if anything contrite about the prior decades' sluggish wage growth, and willing to experiment with potentially more aggressively stimulative policy, like "flexible average inflation targeting".

6. Capital as baby boomers and a new 1970s? (2021 - ?)

Whether policymakers intended or did not intend to shift from the Great Moderation policy regime, that regime performed exactly as designed during the sudden, sharp inflation that began early in 2021 and peaked in the summer of 2022. The Fed raised interest rates and made it clear that they were not interested in supporting asset prices. From January to October 2022, the S&P 500 fell by 25%, and the inflation began to subside, even as the unemployment rate somewhat declined.

It is unknowable3 the degree to which the decline of inflation was due to monetary policy — and the collapse of asset prices and financial income it helped provoke — versus businesses simply working out supply-chain snarls and adjusting to shifts in consumer preference after COVID.

However, something peculiar has happened in the aftermath of the inflation. The demand-deficient 2010s are a lost continent, a strange dream we now barely remember. Perhaps it is not that demand has grown robust, but that supply has grown brittle. To the inflation targeter it's all the same. The economic policy apparatus remains unnerved by the recent inflation and on-guard against a possible resurgence. Under these circumstances, one might have expected — indeed I did expect — that policymakers would not be very eager to see a sharp recovery in asset prices. After the S&P 500 fell in 2022, and then inflation subsided, policymakers could have pocketed that disinflationary impulse. They could have made clear a reluctance to see asset prices soar, and used tools like threats of even higher rates and aggressive quantitative tightening to prevent a new asset price boom.

They have done no such thing. Under both Joe Biden and now Donald Trump, policymakers have accommodated exuberant asset markets.

Very recently, but only very recently, there has been some hint of a potential employment recession. But policymakers accommodated (and of course bragged about) the asset boom long before there was any hint of recession, while the pain of and potential for inflation was still top-of-mind. Why?

In the 1970s, of course we could have stopped the inflation with sufficiently tight policy. We did not, because doing so would have been so economically destructive, or so dangerous to political stability, that enduring the inflation was worth avoiding those costs and risks. The baby boomers had to be employed, at wages that would endow their independence, even if the cost of ensuring that they were was a prolonged inflation with unjust distributional effects.

In 2022, we could have dramatically reduced ongoing inflation risk by simply abstaining from an ascending asset price path, of stock prices and also housing. But, with a few temporary setbacks, we have been on this ascending asset price path since the mid-1980s, and to the most affluent, best enfrachised fractions of our public, the continuing of its ascension has evolved into a kind of social contract. I would guess that a political system under Donald Trump is even more interested in seeing "number go up", and more allergic to asset price declines, than the political system captained by Joe Biden.

So, in a way, we find ourselves back in the 1970s. We don't face inflationary demographics. But we are susceptible to negative supply shocks, due to tariffs, and our determination to decouple from China, and just the error and noise that comes with Donald Trump's improvisational leadership style. Those negative supply shocks will become inflations, unless the policy apparatus can restrain demand to hold the price level steady. But restraining demand now means reining in asset prices, or even encouraging asset price declines, which the American leadership class, including both Republican-coded plutocrats and Democrat-coded professionals, seems unwilling to tolerate beyond very short-term wobbles.

The American public, when composed as an electorate, detests inflation much more than it detests asset price declines or even employment recessions. But it is not the American public that decides these things, and here in 2025, it's not clear how much capacity an increasingly manipulated and gerrymandered and suppressed electorate will have to hold policymakers to account. Our leaders might well choose, or try to choose, booming assets and elevated inflation. Stephen Miran, if not quite choosing that, is choosing to err in that direction.4

Alternatively, if a continuing asset boom is non-negotiable and inflation is absolutely to be avoided, our leaders might choose to use an expansion of inequality as a disinflationary policy instrument. Inequality is disinflationary because of marginal-propensity-to-consume effects. The very rich mostly bank any new income, while the less rich spend what they get, bidding for goods and services. If you can transfer income from the less-rich to the very rich, you reduce bids for scarce goods and services, and so reduce upward pressure on prices.

Withdrawing income from the very poor would have little disinflationary effect. Even though the very poor spend almost all of their income, they don't have enough of it to matter. To use inequality as a disinflationary instrument, you'd want to transfer incomes from the middle class to the very wealthy.

There's nothing new about this. It's part of why the Reagan Revolution was persistently disinflationary. Yawning inequality is much of the reason inflation became so distant a risk since the 1980s, why more frequently than we've had to worry about inflation, we've had to drop interest rates to near zero in order to stimulate.

But now, due to politics and geopolitics, we are at risk of powerful negative supply shocks. We may soon face a choice of tolerating serious inflation, ending our addiction to asset prices, or taking inequality to a whole new level.

More speculatively, if we had any sense, if we weren't idiots, we would forswear all of downwardly rigid wages, inequality-expanding capital income, and household-balance-sheet destroying borrowings as instruments to modulate aggregate demand. We'd adjust some form of transfer income instead.

-

You might object that increasing interest rates also increases creditors' incomes, so wouldn't that stimulate demand? To a degree. But that effect is offset by declining asset values, and especially by the reduction of new borrowers. Borrowers spend the money they borrow. Creditors often just bank the interest they own. This effect might become reversed if the public debt were sufficiently large, and the holders of that debt sufficiently inclined to spend out of marginal income, but so far that has not been the case, and it certainly was not in the 1980s and 1990s.

↩ -

Since 1995, "democratization of credit" has been a very widely used turn of phrase! I can't be sure that Lindsey's is the first use, but Livshits, MacGee, and Tertilt attribute the phrase to him.

↩ -

Yes, I know there are studies that purport to know. As I was saying, it is unknowable.

↩ -

I think there has been a change in political economy since I wrote pieces like "Depression is a choice", "Stabilizing prices is immoral", and "Hard money is not a mistake". In the early post-crisis era, older affluent Americans were I think more tilted towards bonds than they are now, and much more conscious of the risks of equity investing. The generation that has taken their place treats index funds as safe and wise, the thing to be invested in for any horizon longer than about five years. BTFD. Unfortunately, that has not meant we've transitioned from creditors' rentierism to running a broad-based hot economy. It has just meant number must go up, whether it goes up because firms produce in greater quantity at moderate margins, or because they squeeze customers, workers, and vendors to expand margins, or simply via spiraling multiples. Everyone still hates inflation! But while a prior generation would have firmly preferred stagnant equity prices if that's what would insure the real value of their bond portfolios, a new generation has counted its equity chickens long before they'll hatch, and would find a tradeoff between low inflation and index-fund appreciation a closer-run thing.

↩

2025-09-25 @ 12:20 PM EDT