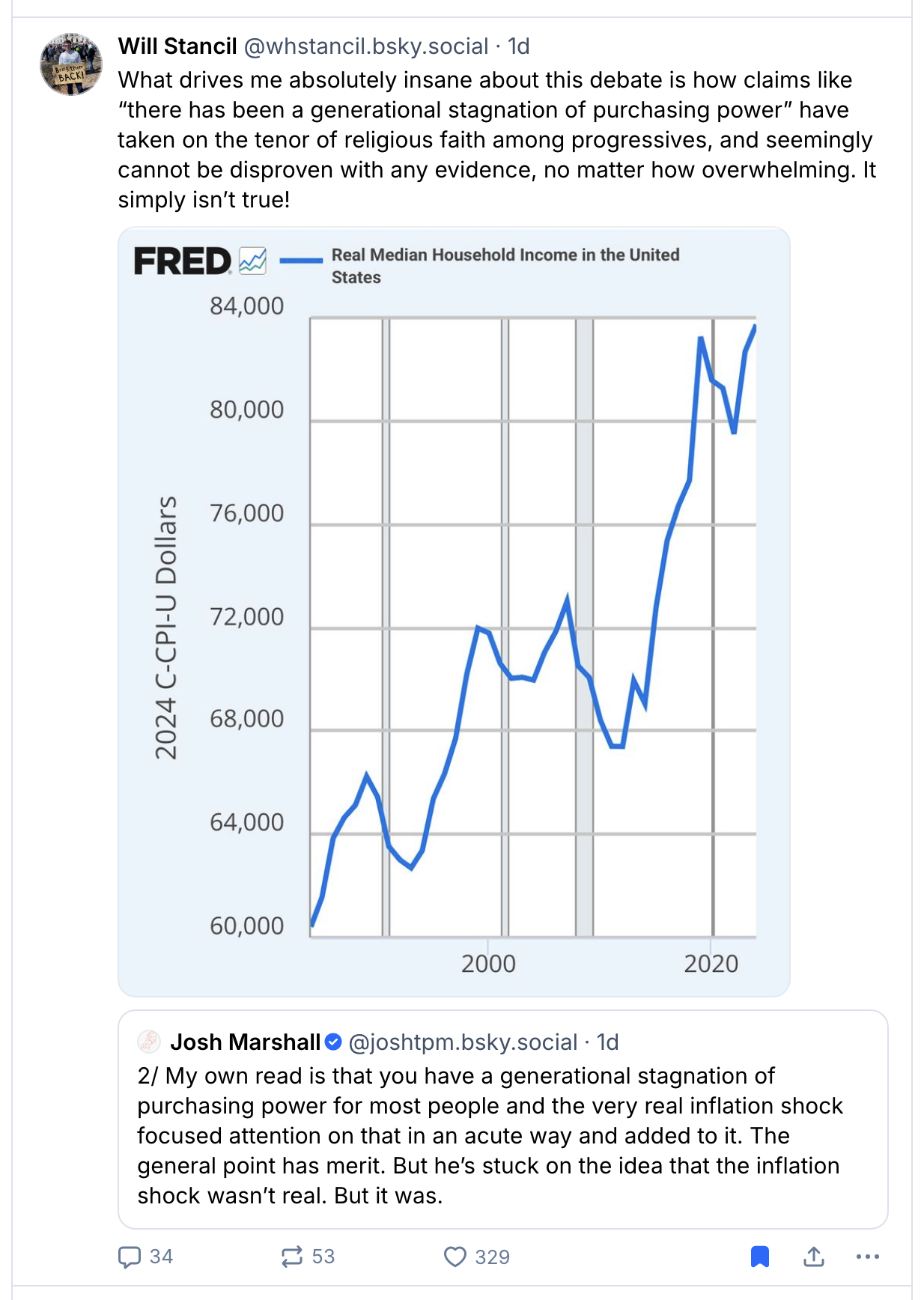

Will Stancil posted the following over the weekend:

I want to offer a straightforward point that a lot of economic controversializing should better take into account.

Over long periods of time, you cannot treat changes in measured "real purchasing power" as equivalent to changes in economic welfare.

This is confusing, because over short periods of time, you can and should! Change in real purchasing power is what you want to look at, when evaluating growth on a year-to-year basis.

But there are slippages in the measure, so that as years accumulate into decades, comparisons become effectively meaningless.

Let's talk about some of those slippages.

- Purchasing power is distinct from welfare, in a manner time varying

- Only the most quantifiable aspects of changes in quality are captured in inflation measures

- Inflation measures abstract away the bundling of goods and services

- Changes in inequality of quality are overlooked

- The composition of price changes has distributional effects

We end with a short conclusion.

1. Purchasing power is distinct from welfare, in a manner time varying

The object of the economy is not dollars and cents, not goods and services. If we built a paperclip maximizer and the paperclip maximizer consumed us all but produced paperclips in quantities such that they would (well would have) sold for ten times current GDP at their final price, that wouldn't actually count as growth.

The object of economics is welfare. We are trying organize production and distribution of goods and services in whatever manner would make human beings "better off".

"Better off" is inherently a normative question. Human welfare per se is not observable. Economics, with its pretensions toward being a "science" has struggled with this for a century.

Nevertheless, you have not said anything of interest if you have said people can buy more "stuff". It has to be the stuff they need, in a manner constitutive of well being.

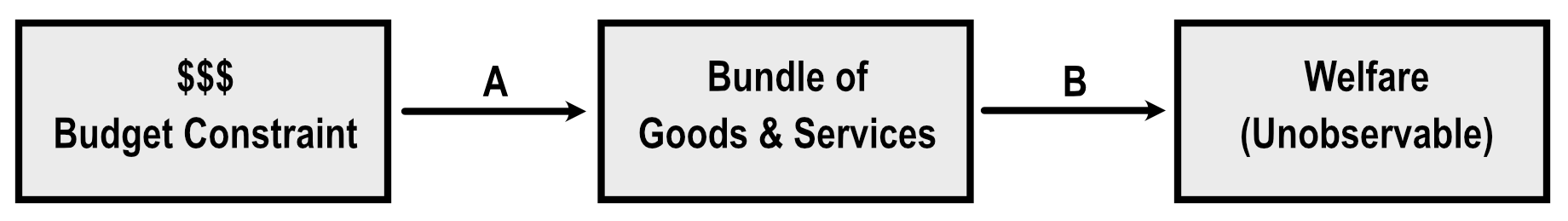

Economists model human behavior in terms of utility maximization. We claim, at any given time, people face a budget constraint. Within that budget constraint they put together a bundle of goods and services that maximizes their "utility". That utility then translates to "welfare", the unobservable, unscientific, well-being that we actually care about, but cannot quantitatively measure.

Measures of real purchasing power can tell us something about Transition A, from a budget constraint to a bundle of goods and services. They can tell us nothing, unfortunately, about Transition B, from a bundle of goods and services to a person's welfare.

Nothing suggests that the relationship between a bundle of goods and the welfare a person derives from it stays the same over time. Obviously it does not. A parent derives well-being from diapers in her consumption basket when her baby is 1 year old, but would not when her child is 11 years old.

So the relationship between the composition of the consumption bundle and welfare is time varying. But so too can the relationship between the value of the consumption bundle and welfare. A twenty year old without children can thrive on a salary that would leave her immiserated when she has one-year-old twins and needs to fund the diapers and formula and child care.

The value of goods and services in welfare terms depends not only on their amount, but also upon the circumstances and obligations of their purchasers.

As individuals we all understand this, but as technocrats, we often fail to aggregate the insight.

Transportation is a large fraction of what we spend money on, roughly 10% of the CPI-U consumption bundle if we include fuel costs. Consider a typical suburban commuter, who drives thirty minutes and twenty miles to and from work every day. A century ago, his doppelganger might have lived in an urban neighborhood, and walked or taken a streetcar to a workplace much closer to his home.

The quantity of transportation our modern commuter purchases with his transportation budget, in terms of miles traveled, is extraordinary, even miraculous, from his antecedent's perspective. Less than ten percent of his wages now purchase miles and miles of point-to-point, off-street-line transportion, which might easily have consumed his entire salary in 1925!

So, in a certain sense, our modern commuter is a whole lot richer. Economic statisticians accurately measure his real consumption bundle as much, much larger than his predecessor's due to the collapse in cost, increase in speed and comfort, of transportation.

But in another respect, our modern commuter is not richer at all. The world has changed. He no longer has the option of taking a job whose quality and pay would support his typical commuter lifestyle absent accepting an obligation to purchase all of those transportation miles. He can purchase a much larger bundle of goods and services than his predecessor could, but he also has to purchase a much larger bundle of goods and services just to live a life that will be welfare comparable.

One can argue that, by the preferences revealed in America's historical suburbanization, our contemporary sprawling life is better than the more compact urban life that preceded it, and actually commuters are gaining welfare roughly in proportion to the vast expansion of transportation miles purchased. One can argue that America's suburbanization reflects political, economic, and social factors beyond individual preference, that are in any case locked into the built environment in ways now exempt from personal choice, and that in fact suburban life is alienating and undesirable, as revealed by the very high cost of housing in compact urban areas that offer similar levels of safety and amenity under a pedestrian lifestyle.

These are live questions! No purchasing power measure can answer them for us.

We get to choose the bundle of goods and services we purchase from our income. Real purchasing power measures can tell us something about "how much" we can buy, although collapsing a very heterogenous mix of goods and services into a single scalar value is always fraught.

But real purchasing power measures do not tell us anything about the circumstances under which we purchase or deploy that bundle of goods and services, how much we require to stay above some waterline of welfare.

And our requirements changes, quite radically. A person with the income, in real terms, of say a successful physician in 1925 would find themselves living in a mobile home park today, and incapable of practicing their profession, even presuming updated skills, for want of any ability to afford prerequisites to participation in terms of transportation, wardrobe, liability insurance, etc.

At an individual level, we understand that an easy mistake a person can make is to let their cost structure increase faster than their means, even as their means increase. If your salary doubles, but you trade up for a more expensive car, a more expensive home, the kids in private schools, you may find yourself in a worse situation than you had been before your raise.

But our economic measures don't consider that we might do this as a society, in ways that override the choices that we might have made individually. Most of us can't really opt out of the cost structures we've collectively established as typical, absent very radical breaks from society that would themselves negatively affect our welfare. Even as our correctly measured, median-not-average real income increases, our actual choice set can grow worse.

2. Only the most quantifiable aspects of changes in quality are captured in inflation measures

Inflation is not correctly measured. In saying that, I cast no shade on the fine econometricians at BLS, who do (and I hope will be permitted to continue to do) great work.

But when constructing measures of the price level, if we fail to take into account adjustments in quality, we'll get things very wrong. BLS does adjust for quality! But they can only do so for characteristics that can be straightforwardly quantified, and their relationship to price modeled. Plus, there are lots of characteristics that plainly affect the quality of our consumption of a good or service that would, for a variety of reasons, be controversial to incorporate into a price measure, and so aren't.

Suppose we faced a new national crime wave that led to a broad-based increase in ones risk of getting mugged or ones house burgled. The risk level has increased similarly basically everywhere. For all of us, then, the value in real terms of our housing will have declined. Nearby crime is definitely a component of the lived quality of housing!

In theory, a price index could take this into account. To hold welfare roughly constant, a person living in what was once a modest crime neighborhood but is now very dangerous could move to a comparable home in what was once a practically crime-free neighborhood but now experiences modest crime. The difference in price between these two otherwise comparable homes would be a measure of how much the change in crime rate had impaired the value of the original home, even though observed home prices might not change much, since since the relative rankings of safety have not changed and everybody still has to live somewhere.

Safety is a big part of what we pay a premium for when choosing a home. The national crime wave makes us all poorer, in terms of qualities of housing we actually pay for. From a conceptual standpoint, if aggregate prices are unchanged, we should treat that as housing inflation. You have to pay more to get the same safety-adjusted home.

But we don't do that. Our thought experiment about how we might quantify the impairment depends upon accurate comparables that would be difficult for a statistical agency to put together. We don't think crime rates are measured very well or consistently across localities.

Crime obviously and profoundly affects the real value of housing services we purchase. Home prices obviously depend, quite a lot, on nearby criminality. But we exclude it from the quality adjustment exercise, and we're unlikely to do anything about that.

This goes both ways! The past few decades have in fact been a tale of decreasing average criminality, despite a post-COVID bump. That has amounted to a large increase in the quality of American housing. It's been a source of overstating inflation.

The point, however, is that aspects of the quality of goods and services unaccounted for by statistical agencies introduce noise, error, into our measures. Over short periods of time this error is likely to be small, but unless we assume without evidence the positive and negative omissions cancel, we should expect our mismeasurement to accumulate and grow over time. Comparisons, then, of "real" purchasing power become more and more surreal, the longer the interval over which they are compared.

3. Inflation measures abstract away the bundling of goods and services

Aspects of housing quality that we can and do adjust for include measurables like square footage. If, over a decade, observed home prices rise by 30%, but the size of the typical home sold also increases by 30%, should that count as home inflation at all? Mostly it doesn't, because BLS adjusts for home sizes. 1

But housing is not in fact a good one buys by the square foot. When one buys a house, or rents an apartment, one must buy or rent all of its square feet. And the square footage of homes available is correlated to other characteristics, like recency of construction, quality of school, nearby crime rate, etc.

A stupid point widely made in the punditocracy is that, if one wanted to live like a middle-class 1950s family on a single middle-class wage, one absolutely could, if one bought that same 1950s home with its 1950s square footage. But one would not actually be buying the same home at all, because the amenities that are the primary source of value for most homes are related to the affluence of ones neighbors. The small single-family home you could still buy at 1950s prices relative to a single middle-class wage earners' wages is very likely in a neighborhood with not-so-great schools, dollar stores rather than a Safeway, some issues with crime.

Suppose a young couple, two incomes but not huge incomes, wants to buy a home in a new neighborhood with great schools. They could afford to buy in the neighborhood the thousand square feet that was typical of a single family home in the 1950s, at the current going rate per square foot. Unfortunately, our couple would likely find that there are no homes smaller than 2000 square feet in an upscale new single family home development.

Our real purchasing power measures presume that they could buy such a home. But in practice, they have to buy twice the home they would have preferred in order to obtain the other goods bundled with housing. They are significantly poorer than their headline CPI adjusted wage suggests, because the methodologies behind inflation indices assume purchasers can independently set the quantities of goods purchased over a continual range, and often that they can substitute at will.

In unequal and class stratified societies, it is often the case that a few choices — in what kind of home one lives and near whom, what means of transportation you employ — segments whole classes of typical consumption bundles, in ways that sometimes seem perverse. For example, in the US, one can eat very cheaply if one stocks up on bulk goods from Costco. But to do so, one wants to live not so far from a Costco, have something like an SUV, have storage for bulk and also refrigerated goods, have financial liquidity one can afford to tie up in inventory. The low cost of bulk Costco purchases is correctly factored into the average that forms CPI grocery prices, but is inaccessible in practice to people who've selected (through lower cost housing and transportation) into a different consumption bundle.

Again, over short periods of time, the bundles are what they are, they remain pretty constant so measured changes in the price level effectively control for this.

But over longer periods of time, the whole structure of these bundles shift around, introducing error into comparisons of "real purchasing power".

4. Changes in inequality of quality are overlooked

Charles Murray, whatever else one might have to say about him, wrote a good book in "Coming Apart". Among other observations, Murray pointed out that American success was increasingly concentrating into "super zips". A few concentrated geographies were becoming enclaves of the well-to-do, while the rest of the country languished.

Let's consider how this dynamic might affect inflation and therefore "real purchasing power" measures, versus how it might affect welfare.

Everyone must be housed, and to a first approximation, the housing stock of the country matches the number of households. Houses are a game of musical chairs: Absent a serious surplus — which is very far from our problem — roughly all the houses will be occupied. (Yes, second homes exist, and some homes fall into disused vacancy, but these categories are small, and if anything they exacerbate the dynamic we'll describe.)

So, if a small fraction of the houses, for whatever reason, become much more desirable than the rest, their prices will be bid up. However, there is no reason to think that the average price of housing will increase. The purchasing power devoted to paying up for housing in the "super zips" is purchasing power no longer directed to housing elsewhere. If we hold the aggregate housing budget constant, the effect would be home prices in the desirable areas would spike, while housing prices in the rest of the country would fall a bit, so the average cost of housing remains unchanged.

In practice, the aggregate housing budget, even for existing homes, is not held constant. Soaring top inequality helps ensure prices of the most desirable homes are continually bid upward. Our financial system lends purchasing power to home buyers at an increasing rate, a rate that for the past four decades has exceeded the rate of inflation. Housing prices in aggregate rise.

But the effect we've described still holds: Housing prices in "super zips" rise much faster than elsewhere, housing prices elsewhere increase more slowly, as so much of the aggregate bid on housing flows to premium enclaves. An average ends up in our inflation index.

If we hold the quality of housing constant, this distributional oddity translates to an increase in most homebuyers purchasing power. Rich peoples' odd fetish with "super zips" means that housing is cheaper everywhere else for everyone else than otherwise it would have been. Noah Smith famously made this point with his "yuppy fishtank" metaphor. Normal people should delight as yuppies and tech bros and other people with more money than sense waste their housing dollars in a few overpriced districts. It prevents the rest of us from having to compete with their vast pocketbooks if we want a bit of space.

However, as Murray observed, we don't in practice hold the quality of housing constant. The quality of housing is largely a function of who your neighbors are and how that shapes the parks, schools, commercial amenities, social and employment opportunities that surround you. Well-to-do people are not in fact concentrating themselves into these few districts because they are fucking weirdoes who like to be fucking weirdoes. They are doing so because there is a network effect. The more people with resources you put together in a tight geography, the more likely it's going to be a safe, appealing place to live with good schools and good jobs. When those resources withdraw themselves from the rest of the country to enjoy this network effect, the rest of the country suffers a loss in quality. Safeways get replaced by Whole Foods on one side of the divide, by Dollar Trees on the other.

Housing price increases come to have a bimodal distribution, a high rate for coveted geographies, a lower rate everywhere else. The measured average rate of housing inflation is a correct average, but matches lived experience on neither side of the divide. The median household is likely to experience a lower rate of housing price increases than is included in the measure.

However, before we pronounce on the correctness of the measure for any household, we also have to adjust for quality. It could be the case that the relative decline in quality of non-super-zip areas exactly matches the slower-than-average price appreciation, so the inflation measure is in fact correct for the median household!

But it could also be the case that the decline in quality of households in less coveted locales more than offsets the lower-than-average rate of home price increases, in which case headline real purchasing power for the median household would be overstated.

The same is true for wealthy areas. It could be that the increase in quality due to rich-people network effects exactly matches the higher-than-average rate of price increase, and so the headline inflation measure is correct for these households. It could be that rich people getting together and sharing lattes and nice parks is so awesome that the quality difference outpaces the above average home price appreciation, and so measured inflation is overstated for these regions.

It could also be the case that there are diminishing returns to rich-people network effects, so that over time the quality increase fails to match the high rate of home price appreciation, so their true rate of housing inflation is higher than the headline measure.

Note that there is no necessary relationship between quality changes in the two regions. Nothing compels a loss in quality in less coveted geographies to be in any sense "equal to" a gain in quality in the special places. It could be that rich people leaving affects the quality of life in less pricey places not at all, so rich people self-segregating amounts to a positive sum change, they enjoy nicer parks at no cost to anyone. It could, however, be the case that better-resourced people segregating away has a very large negative effect on the places they abandon, which more than offsets, in aggregate terms, the benefits the wealthy enjoy in their enclaves. If this is the case, the dynamic could make us in aggregate much poorer, while our real median purchasing power measures remain entirely oblivious.

5. The composition of price changes has distributional effects

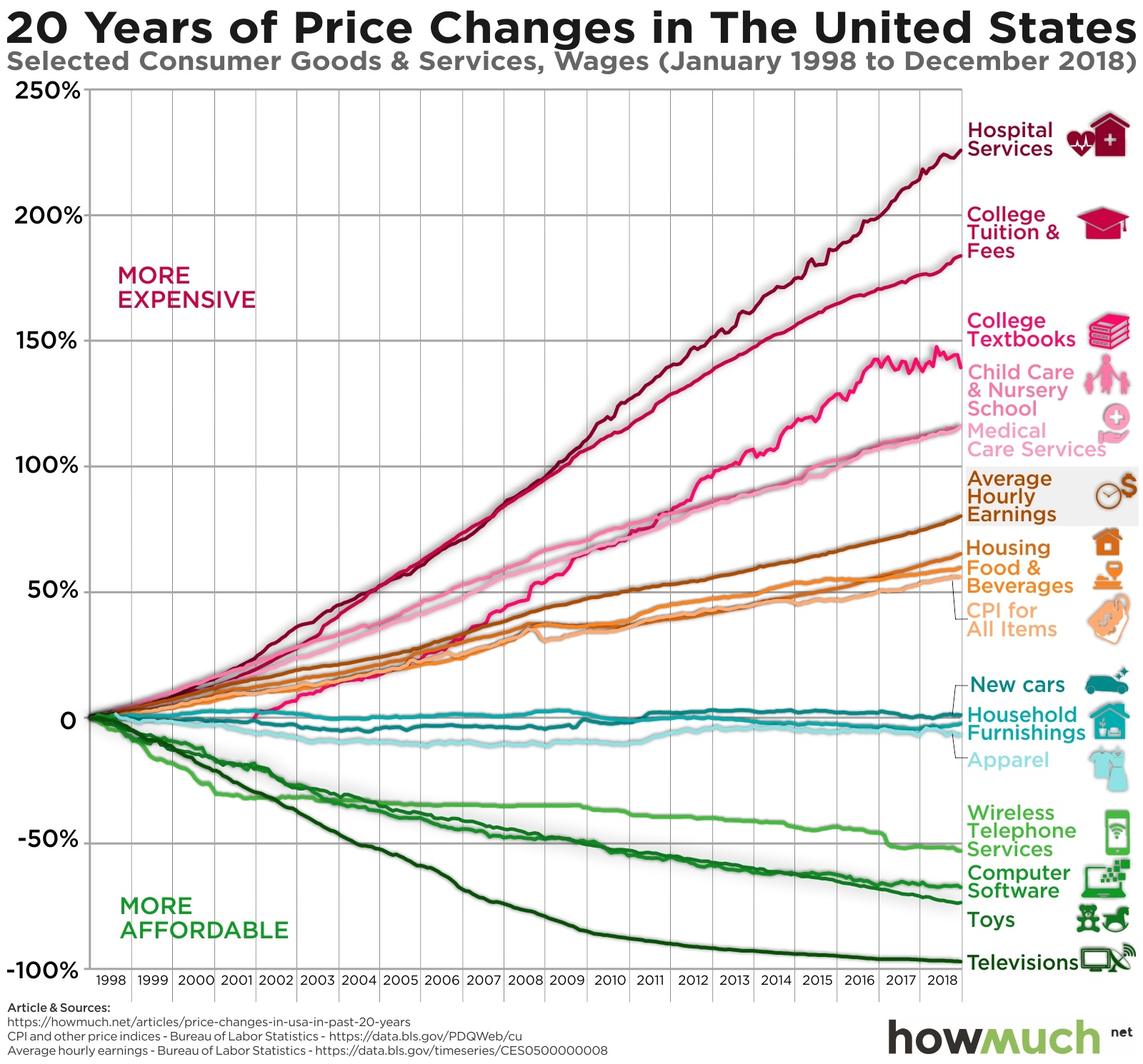

Among other responses to Stancil's post above was this (in)famous graph, taken from the Baumol effect Wikipedia page:

"Real" purchasing power is based on the average price of some bundle of goods, usually allowing for some degree of substitution between similar goods. Even while the average stays relatively stable, prices of the components of the bundle can vary widely. As the graph shows, some things have grown much more expensive, while others have grown much cheaper, even while the overall price level ("CPI for All Items" in the graph) changed less dramatically.

Further, the composition of the bundle replicates what an average rather than median purchaser might buy, which has important distributional consequences.

It's worth unpacking this a bit. In the econo-micro-blogosphere, there's a typical dialog that goes something like this:

Apologist: [posts graph like Stancil's at the top of this piece]

Agonist: You say that incomes have grown, but that's just because, like, Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos have gotten so rich.

Apologist: It's median income. Do you even know what a median is, ya fuckin' commie?

[Suddenly in His Infinite Patience, Matt Darling appears to explain what a median is.]

"Apologist" is right that the income measure she has chosen is a median, and so is unaffected by Musk and Bezos' hypertrophied extraction.

But there is a wrinkle! The very units of that measure are based on average purchasing habits, which mean they are skewed to the purchasing habits of the relatively rich who, unsuprisingly, spend a disproportionate share of the money spent on consumer goods!

(See Nathan Tankus, Eduardo Ley.)

The less rich spend a greater much fraction of their wealth on necessities and inferior goods than the wealthy do. A quick glance at the graph above confirms that prices have tended to increase quickly for the necessities that consume a large share of the median consumer's budget, while we've enjoyed outright deflation in more discretionary goods. So "median household real income" is overstated for the median consumer, because its very units are biased toward the experience of the better off.

This bias would disappear if variability in the rate of price changes happened to be orthogonal to differences in the consumption bundle between the rich and less rich, but that is unlikely ever to be the case. Independence of variables in social affairs is the rare exception, not the rule.

The direction of the bias could invert if high-budget-share necessity prices grow more slowly than the prices of discretionary goods. But for the past decades, the pattern of facts means that "median real household income" measures are overstated for the median household.

The size of this bias will be related to the level of consumption inequality. We have interminable arguments over whether inequality is increasing or decreasing, and what kinds of inequality count. Under Biden, wage inequality compressed for a while, but comprehensive income inequality tends to be driven more by asset valuation changes, and home prices boomed. Although the recent claim that the top 10% account for 50% of consumer spending is almost certainly overstated, consumption inequality in the US is high, and has likely been growing over the last few decades. If consumption inequality increases while inflation hits necessities more than discretionary items, both trends will reinforce one another in exaggerating measures of "real median household income".

Stancil writes

The American economy is much larger than a few decades ago and much of those gains (not enough! But a lot) have been spread across the income distribution. Economically speaking, you’d almost certainly rather live today than any prior time.

That's his point of view. It might be right! What we measure as GDP is, factually, larger than it ever has been.

But any claim that things are "better" for the typical American is an opinion, one you can try to muster various sorts of evidence to support, but on which you can't pull rank — because science, data — and coronate as fact.

A lot of people — yes, a lot of us, I number among them — disagree that these are materially the best of times in the good ol' US of A. There is evidence on our side too. Suicide rates have been on a consistent uptrend. The political upheavals we've experienced might have other-than-material causes. But it does suggest a lot of us might not perceive our circumstances as too wonderful if more of us want to kill ourselves and the public seems willing to risk burning it all down just for the possibility of a change.

Whatever we are doing seems not to be conducive of welfare, and economics ultimately is the science of organizing production and consumption in the service of human welfare. If our measures say everything is awesome, we might hope for more discerning measures.

I guess you can argue that things really are awesome and we are last men, blowing it all up out of ennui, because we are too comfortable. I'd gently suggest you are mistaken. From my perspective, if this is your view, you don't live in the world. In the world I inhabit, even the objectively affluent suffer astonishing levels of financial distress. Lots of people aren't objectively affluent, perceive themselves as losers in the richest country ever, do consider suicide. The cost structure of contemporary American life pushes us all to become grifters. Whether we succeed or fail, what is surely unaffordable is to be good people.

Whichever side of the argument you take — on this as on most social questions — what we can observe definitively in factual terms is unlikely to be dispositive.

This is why we have democracy in the first place. Ultimately human welfare is a matter of subjectivities. We require our subjectivities to be incorporated in the policymaking process if the polity is to thrive. You are a bad technocrat if you imagine you can substitute your technocratic measures for those subjectivities. Your job is to grope for a reconciliation between the objective constraints about which you may in fact be expert and the subjective outcomes that are ultimately policy's purpose.

I'm happy to concede that most Americans can buy "more stuff" in some sense than ever before. The typical household can buy a lot more televisions. But it is perfectly possible — I think probable, I think obvious — that matching the stuff you can buy with the prerequisites of a materially secure, comfortable life has become much harder for the typical person than it was even in the relatively recent past.

Stancil — and you dear reader! — are free to disagree. I certainly will not claim that I can prove you factually wrong.

I do think I can reject Stancil's assertion that "claims like 'there has been a generational stagnation of purchasing power'" are somehow a shibboleth of the progressive side of economic debates. Let's hear from Rod Dreher, a "post-liberal" on the Orbanist right, speaking with a young conservative:

I asked one astute Zoomer what the Groypers actually wanted (meaning, what were their demands). He said, “They don’t have any. They just want to tear everything down.”

Then he went on to explain in calm, rational detail why his generation is so utterly screwed. The problems are mostly economic and material, in his view (and this is something echoed by other conversations). They don’t have good career prospects, they’ll probably never be able to buy a home, many are heavily indebted with student loans that they were advised by authorities to take out, and the idea that they are likely to marry and start families seems increasingly remote.

If our economic miseries are only mass delusion, it is delusion more widespread than the progressives with whom Stancil so remarkably squabbles online.

-

It's more complicated than this, BLS adjusts for number of rooms, rather than square feet directly, and the cost of owned homes is imputed as rents foregone rather than based on sales price. But conceptually, BLS tries to control for changes in home size.

↩

2025-11-12 @ 03:40 PM EST